Spilt milk

Dairy suppliers Murray Goulburn and Fonterra shocked the dairy community in 2016 by dramatically reducing the farm gate milk price they would pay to farmers. Two years later, Tasmania's dairy industry is on the road to recovery.

Tasmania's agricultural 'Disneyland', Agfest, was dampened two years ago, not by rain but by shocking news for dairy farmers.

Each year, the state's farmers converge on the three-day agricultural festival, held usually in wet weather in May.

On April 26, 2016, dairy processor giant Murray Goulburn announced to its suppliers that it would cut the farm gate milk price for the 2016-17 season.

Murray Goulburn announced it was no longer able to buy milk from farmers at the existing price of $5.60 and now expected it would only be able to pay farmers between $4.50 and $4.75 per kilogram of milk solids (kgMS).

This would put the price of milk below the cost of production for many of the state's farmers and meant each day a farm milked its cows, it would be at a loss.

Worry, concern, and disbelief ran as an undercurrent through the 2016 Agfest festival, which is usually spent by many as a fun weekend away from the farm.

Dairy features strongly at each festival, with an entire tent dedicated to Dairy Australia, Dairy Tasmania and various dairy producers, such as Ashgrove and Pyengana Dairy.

Sixth-generation Legana farmer Joe Hammond, who supplies Fonterra, said at the time he mostly felt disbelief when he heard the news.

“I remember, they announced it on the first day of Agfest [in 2016] and nobody realised what was going on, it was just a sense of disbelief,” he said.

Mr Hammond said as people realised what was going on, the positive vibe of Agfest was affected.

"People were just so shocked, we didn't really know what was going on," he said.

Mr Hammond said in his 15 years as a dairy farmer he had never seen a price cut as dramatic.

He hopes he never will see it again.

While the Murray Goulburn news sent ripples through the dairy community, it wasn't until a week later that Tasmania's largest dairy processor, Fonterra, followed suit with the shock cuts.

Fonterra announced to its suppliers that it would also be reducing the global milk price from $5.60kgMS to just $5kgMS, effective immediately.

At the time, Dairy Tasmania executive officer Mark Smith said the industry would take a $40 million hit.

The dairy industry in Tasmania had seen unprecedented growth in the years leading up to 2016 and contributed about 900 million litres of milk solids in 2015.

“The serious dairy people will ride it through but in the meantime it will impact some businesses severely,” Mr Smith said.

He said, at the time, he suspected some dairy farmers would be pushed out of the market due to the price cuts.

To add insult to injury, Murray Goulburn also announced its controversial Milk Supply Support Payments, which would soon be dubbed the unpopular "claw back scheme".

The price cuts, for Murray Goulburn suppliers, would be also be retrospective and applied for the entire 2016-17 season, not just for the last two months, which many had hoped for.

The MSSP payment would be a loan scheme that farmers would have to pay, on top of their sudden deficit to pay back "what they owed" to the company.

This "claw back" was for milk that had already been paid for. The scheme drew the ire of many dairy farmers in Tasmania.

Primary Industries Minister Jeremy Rockliff said in 2016 there was inherent volatility in the dairy sector and while the drop in price was disappointing he was confident the industry could rebound.

“It will have an impact, the industry will take a hit,” he said.

“But investment is there and it is strong ... we expect the price will recover.”

Mr Rockliff said it was always challenging when the global price was determined by supply and demand, but said Tasmania was a world leader and significant contributor to the world’s global supply of dairy products and would continue to be in the future.

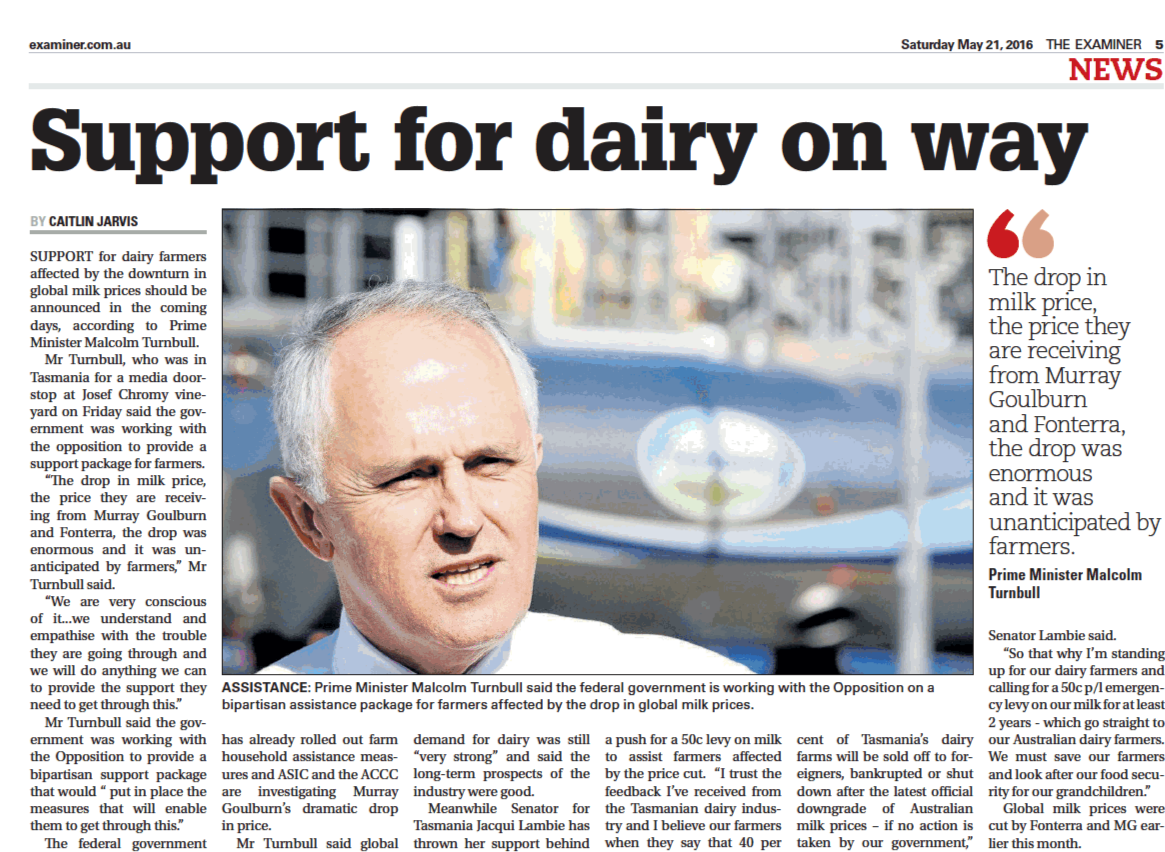

The news of the price drop drew the attention of Canberra, with Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announcing a support package for dairy farmers during a visit to Tasmania in May.

Dairy farmers Byron and Danielle Carins in the Brisbane Street Mall, Launceston.

A few days after the announcement of the shock cuts, Winnaleah dairy farmers Byron and Danielle Carins took to the streets of Launceston to raise awareness of their plight.

The pair, along with their children, protested in the Brisbane Street Mall gathering signatures for a petition to be sent to the government to review the pricing structure for the industry.

The farm gate milk price is set by global supply and demand and is regulated by the larger companies.

It is the price the processor is prepared to pay farmers for the quantity of milk solids in their milk.

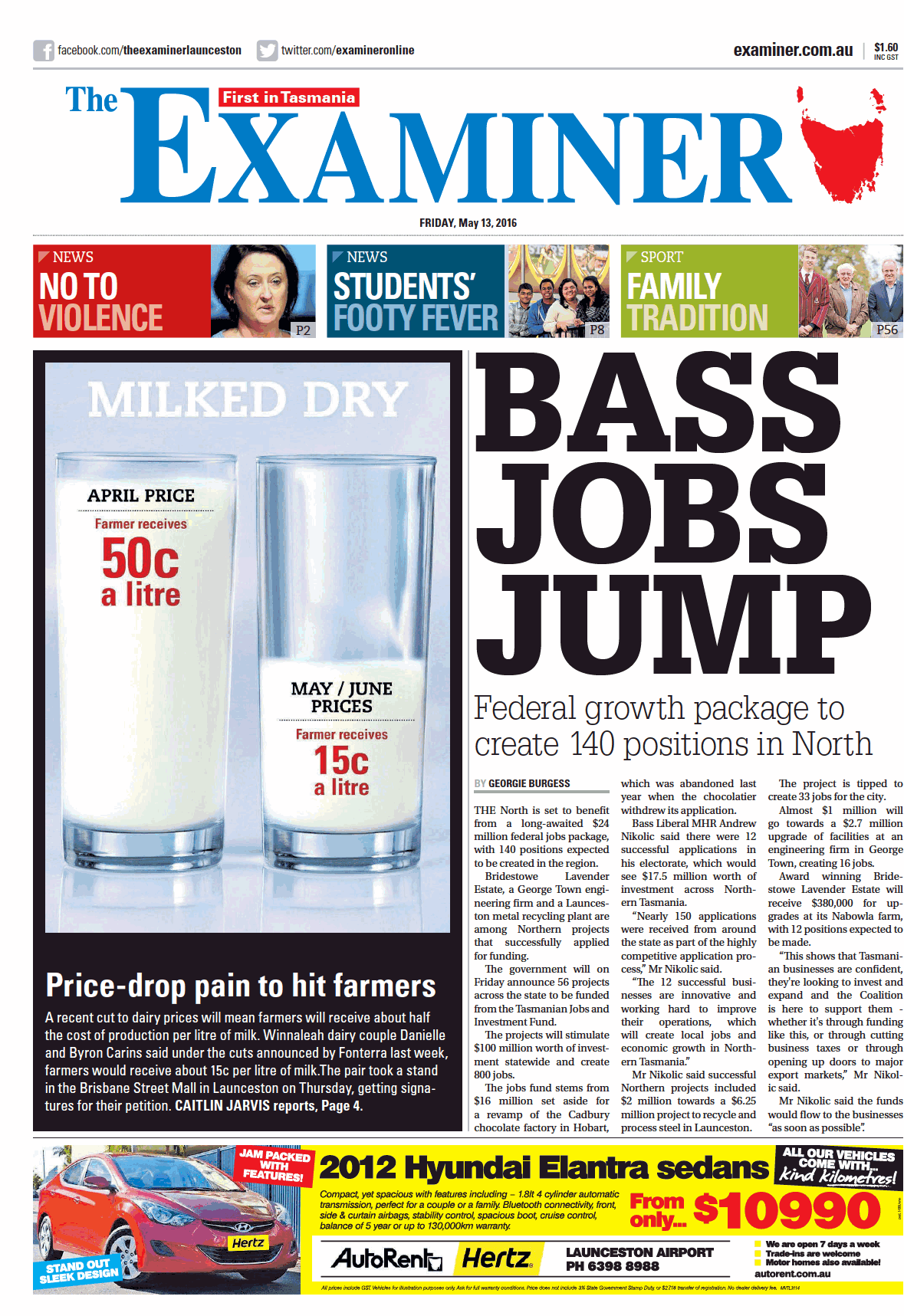

Mr Carins said this reduction meant the farm gate milk price for May and June would be $1.91kgMS for the last two months of the season.

In term of milk production, Mrs Carins said farmers were being paid 55c per litre of milk prior to April.

With the reduction the May and June price would be just 15c. Milk costs at least an average of 30c per litre to produce.

As a result, the Winnaleah farmers had to let go of four employees, dry off their cows two months ahead of schedule as they struggled to not go further into debt due to the spiralling milk price.

The family runs two dairies in the North-East, along with Mr Carins' brother and parents.

A video of Mrs Carins published by The Examiner had strong engagement with readers online.

The video was shared 2815 times, viewed 131,000 times and had 1477 reactions.

Mrs Carins would also take the fight to Canberra, joining a national rally protest in the weeks following the cuts.

The rally comprised hundreds of dairy farmers from across the country who were seeking a review of the pricing structure for dairy farmers.

The year 2016 was not kind to Tasmanian farmers.

Before the price cuts that sent shockwaves through the dairy industry, the state endured the worst flood disaster in 100 years.

Three lives were lost, as were hundreds of livestock from across sectors. Livestock saleyards at Quoiba and Powranna became havens for displaced livestock that had survived the floods.

Roberts livestock managers decided to open both saleyards after learning of the hundreds of animals who were lost and swept away by the flash flooding that struck across the North-West and North.

Coordinator Ebony Bannister said she decided she needed to do something to help the livestock after seeing and learning of the large number of deaths that occurred during the flooding.

Rural Alive and Well chief executive Liz Little, said environmental disasters had a huge impact on farmers.

"I come off a sheep and cattle property in the dry lands of western NSW. We lost our first house to floods and we lived through fire and we saw herds of kangaroos and locust plagues coming out of the South Australian desert," she said.

She said there was a range of determinants that impacted rural communities and wellbeing of the state's farmers.

"Rural businesses and agricultural businesses are the only businesses, other than small shop owners, where you have 24-hour a day home/work/business - they’re all the same thing," she said.

"There’s a whole range of things that impact on that particular set up in terms of a life quality, such as drought, floods and fire, people lose their income, they lose their home, they lose that all at the same time, the economic and financial factors, including industry changes and shut down, like the Murray Goulburn close down.

"We have been doing that type of work in Tasmania for a number of years."

Ms Little said the stresses and strains involved in farming did have an impact on family pressure and domestic violence.

"I understand the impacts of natural disasters on families looking down the barrel of economic destitution and a whole range of things. We’re no clinical organisation. [RAW doesn’t] come out in white coats, and we don’t sound like we’re white coats; we’re there to talk with people in a way they can understand an engage. We are a creature created by farmers and we reflect that. We are uniquely Tasmanian."

Two years on, and Mr Hammond said a sense of disbelief was still there among some suppliers.

“The trust just isn’t there anymore for some people,” he said.

“A lot of people are still quite angry about it.”

In 2016, the Hammonds were milking 485 cows twice a day at their 280-hectare property.

After the milk price crash they were forced to milk once a day and sell off a lot of cows to try and mitigate the loss.

“We were also feeding a lot of grain so we had to try and cut back on the amount we were using,” Mr Hammond said.

While some other farmers were able to dry off their cows and end the season early, that wasn’t an option for the Hammonds.

“We had only calved in March, so, we couldn’t just stop milking. They were all fresh cows,” he said.

He said deciding to stop feeding the cows grain was one of the mitigation steps he made but at the end there wasn’t a lot any farmer could do.

“It did effect our mating and then that flows onto the next year and the next,” he said.

“We are probably only back on track now, two years later.”

This year, the Hammonds are on track to produce three million litres of milk and have a 600-strong dairy herd.

Since the milk price crash, the property has permanently reduced its reliance on grain, that helps its bottom line.

“We have done some re-pasturing and rotational crops, so we rely a bit more on pasture for feed,” Mr Hammond said.

The impacts of the price crash are still fresh in his mind but the business model has recovered, which is testament to the resilience of dairy farming.

Despite the unexpected challenges over the past couple of years, the dairy industry's characteristic resilience is shining through.

Dairy Tasmania chief executive Jonathon Price said production was back on the increase, due to, in fact, higher milk prices and savings on input costs.

"This year production between July 2017 and February 2018 is six per cent above the same time last year, with production year to date of 630.5 million litres," he said.

Mr Price said the highest production year on record was 2014-15 when farmers produced a record-breaking 628.5 million litres.

"Based on this we are on track to exceed the highest annual production of 891 million litres by the end of the year," he said.

"In the last two years there has been a number of large corporate entities purchases farms in Tasmania and continued investment by processors."

Improved farm gate milk prices in 2017-18 season and favourable costs (grain, interest rates etc) have increased supplier confidence.

Mr Price said the recovery and industry improvement supported the view that there was more room for growth for Tasmanian dairy farmers.

"We need to deliver the right training programs to support dairy farmers and for those looking to grow, we need to make sure they have the skills to run their businesses by accessing the right training."

Montagu dairy farmers Jane and Dave Field moved to Tasmania from New Zealand four-and-a-half years ago and quickly jumped into establishing an 800-hectare dairy property.

The Fields are the 2018 DairyTas and Dairy Australia Focus Farmers, which means they are part of farming network around Australia that supports farmer decision making, with an emphasis on tracking real decisions on real farms under real conditions.

At peak, the Fields milk 1400 cows and they are one year into a process that will see them change to a once-a-day milking system.

“Because the farm is so large we always thought we had the potential to milk a lot of cows once a day,” Mr Field said.

While the transition to their new system will take three years, the Fields are committed to improving their farm and work/life balance for themselves and their staff through innovation and training.

“In the first five months we could see that we could make it work. We’ve been doing this since we bought the farm and will continue for another two to three years," Mr Field said.

Changes to their milking system have been supported through farm infrastructure improvements, such as irrigation and drainage.

“Irrigation is a huge game changer. It’s about the amount of pasture you can grow and the quality; it gives you more control."

“It can get very wet and very dry here. If you have good drainage and good irrigation it helps. Good infrastructure and keeping it simple works.”

Staffing stability is important to the Fields, who know they need to keep work interesting.

“Innovation makes farming fun - it keeps people interested in the business. You can’t expect staff to battle with poor infrastructure if it’s not suitable, so you should make it sustainable and profitable," Mr Field said.

The Fields undertake ongoing training programs to keep on top of industry changes and train staff to succeed others moving on to new positions at the farm.

“Because we’re a large farm we employ quite a few staff. How can people thrive in our business if they don’t see a future?”

“I had to learn to be a good staff manager. We attend discussion groups to learn more and get off the farm to network with others," he said.

The potential of Tasmania's dairy industry has been a driver for the Fields - and they predict big things, but know that success still hinges on the milk price.

“We see the Tasmanian dairy industry being strong and growing over the next five to 10 years due to our ability to grow pasture and add value to our products," Mr Field said.

“The sale of Murray Goulburn is about to change our structure. Saputo will be good for competition. We need a sustainable milk price in the long term.”

The best thing about farmers is that they are always trying new things.

In an industry such as dairy, where the volatile market can become a game changer so quickly, some Tasmanian producers have value added products to help mitigate any market changes.

Others have diversified into other crops or products, or removed themselves from the equation altogether.

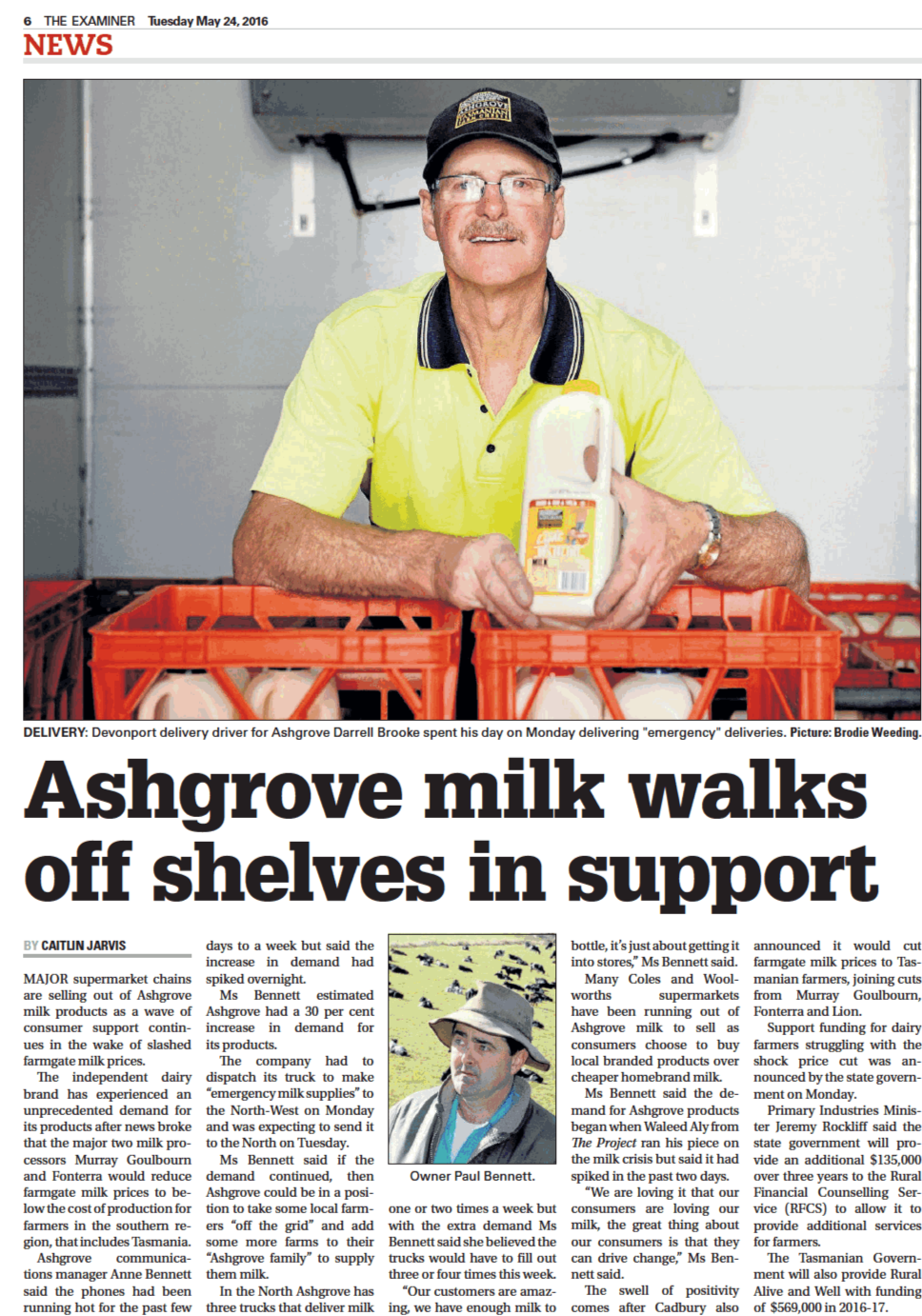

Ashgrove Cheese at Elizabeth Town was an unexpected winner out of the dairy price crash of 2016.

Ashgrove Cheese chairman Paul Bennett built the cheese shop with his father John Bennett 30 years ago.

The independent dairy brand experienced an unprecedented demand for its products after news broke the major two milk processors Murray Goulbourn and Fonterra would reduce farmgate milk prices to below the cost of production.

Ashgrove is Tasmania's largest independent dairy brand and hooks into the tourist market with a "cellar door" for its cheese and dairy products.

However, that tourist market is set to expand, after Ashgrove announced in 2018 it was expanding its "dairy door".

The $1.19 million state-of-the-art complex will become a tourist mecca at its Elizabeth Town site.

As one of four Meander Valley organisations to receive funding under the federal government Regional Jobs and Investment Packages, Ashgrove has plans to capitalise on its Cradle to Coast Tasting Trail position. Ashgrove Cheese received a $565,000 grant and will invest $620,000 to construct and fit out the complex.

Project manager Anne Bennett has been working on plans for the dairy door for years.

“It enables Ashgrove to really bring forward a flagship project that we’ve had on the cards for two years. It will develop the Ashgrove Cheese shop into an iconic Northern Tasmanian tourist destination,” Ms Bennett said.

The complex will almost double the existing shop and factory footprint with experiential, retail, food and outdoor areas that link Ashgrove’s dairy products direct to the farm.

“We are going to bring the farm alive inside the building using technology like virtual reality, augmented reality and cow tracking,” Ms Bennett said.

Tasmania’s newest dairy brand OMG launched just before Christmas 2017, and just over a month into operation they are more than happy with their decision.

The idea for the brand was cooked up between Lileah dairy farmer Gary Watson and Flowerdale dairy farmer Simon Elphinstone.

“We met from a common interest in organic dairy farming,” Mr Elphinstone said.

“We had both converted to organic production but didn’t have a processor for our milk, so we decided to do it ourselves.”

The Lileah property has a combination of spring and autumn calvers to ensure an ongoing flow of milk during autumn for the OMG brand.

This was achieved through undertaking a six-week mating and artificial insemination program for the past two seasons, but resulted in “25 per cent empties”, which is considered good for the time frame.

OMG milk is not homogenised and has no cream taken out, so each bottle contains a thick layer of cream on top.

“It comes off the farm, is pasteurised and then bottled.”

Between their 550 cows, OMG produces "a few million litres" of milk per year.

With innovation like OMG, Ashgrove, and the number of other dairy producers in Tasmania, the industry is in safe hands.