MOTHER Nature is in one of her moods - cranky and showing no respect. For hours, she has furiously lashed out with 110kmh winds from deep in the southern Tasman Sea to buffet the east coast.

And now, as a murky dawn creeps in and Newcastle wakes to a filthy Friday morning, she turns her fury on to a 40,000-tonne Panamanian-registered carrier.

The Pasha Bulker - once a 225-metre-long symbol of man’s power over the oceans - is now a defenceless cork in a vast bathtub, floundering off a brutal coastline and just minutes from stubbornly entering Hunter folklore.

Veteran newsman Greg Wendt first hears of this ghost of the darkness from some old salts at Merewether Surf Club as he cowers in the winds waiting for his morning coffee.

They tell Wendt the big red ship had earlier found itself just off the famous surf break, battling the gales and 10-metre swells as its captain tried valiantly to get the propeller of the unladen carrier, already very high in the water, to gain some traction and send her back out to the relative safety of open water.

Wendt heads into work at the Newcastle Herald to find phones ringing off the hook. Word of the Pasha’s fight headed up the coast quicker than the swells could push her.

With photographer David Wicks, Wendt speeds passed the old Royal Newcastle Hospital and down Shortland Esplanade to be greeted by a sight so vivid it has burnt in his memory.

“There is this 40,000-tonne bulk carrier just floundering almost. Battered by big waves and looking like it was perilously close to the baths. And in trouble.’’

“The captain of the ship was trying to reverse it and then jerk the bow into the teeth of the storm, so he was reversing down towards Nobbys.

“There is a great shot that [former Herald photographer Darren Pateman] got of the Pasha Bulker being hit by a wave and was bent almost over the rocks at the Cowrie Hole.

“I thought that’s where it is going to end up. But it kept going in reverse towards Nobbys at a rate of knots.

“This wave just swamped it and all you could see was a bit of the funnel and a little bit of the bow and then it disappeared in the murk towards Nobbys.’’

Former police officer and Nobbys Surf Life Saving Club president Dave Edwards is around the corner, rechecking the club’s windows as he tries to give them every possible chance to survive the growing storm.

“I came up to the kiosk after I closed the club up and spoke to the girl in the kiosk and when I was talking to her I saw the big red ship getting pushed back past Groper Rock and was getting blown backwards,’’ Edwards says.

“The girl who was at the kiosk saw it as well and all we could say, well, there were a few swear words.

“I had driven by the baths and I could see it out the back of the baths but it didn’t register to me how close it was, I was too intent to get around here in the wind and the rain to secure the surf club.

“But as time marched on I came down the kiosk and looked through the kiosk and there she was.’’

Wendt and Edwards quickly become part of a growing crowd of onlookers caught in the awesome moment.

Wendt remembers: “It was unbelievable, and it was more unbelievable that it was happening in front of everyone who were just standing there with hands on their mouths.’’

But to Edwards, a veteran of decades of police work with a passion of Nobbys Beach and its iconic status, these were worrying moments.

He watches, hoping against hope it does not run aground between the Cowrie Hole and Nobbys Beach “because we could have still been picking it off the rock shelf’’.

“It was getting hit by these massive sets because Nobbys, when we get big seas the swell gets that big it breaks in one massive wave. And that is what occurred here,’’ he says.

“There were a number of set waves and it got hit sideways and got pushed in slightly, got hit again and then there was a break.

“There was a definite break in the sets.

“ And whilst I was still in the doors of the kiosk, the engines, the propeller, took grip and for 30 seconds or so it started to move forward across the bay here.

“And I thought ‘my God, it’s going to come aground here in the corner’.

“This massive great bow coming directly for us. Then, again, the sets came and hit it again. Bang, bang. And again. Bang, bang.’’

In all the “bad positions”, the Pasha lands “in the best of those bad positions’’.

But even through the howling gales strong enough to hurl people across the slippery pavement, the noises from the Pasha emanate.

Wendt says you could hear the moans of buckling steel and concerns move to whether, like the infamous Sygna which crashed into Stockton Beach 33 years previous, the big girl would break up.

“But the Pasha Bulker was a fairly new ship and apparently that might have helped a little bit.

“It was also sitting on some sand so the back half of it was jammed on the reef and the propeller had gouged into the reef.

“But you could hear the buckling and just the thunderous roar of the ocean hitting it, slamming into the side of it.’’

The cavalry quickly arrive - Edwards helping to set up a command post for emergency services as authorities work out how to get the 22 Filipino seamen off.

Two Westpac rescue helicopters hover overhead and the rescue operation begins with crewman Glen Ramplin beginning the first of seemingly endless descents onto the deck to start carrying the seamen to safety.

“[Helicopter crew chief] Graham Nickisson said every time [Ramplin] went down the rope and touched the ship he got a massive electric shock because the blades had set up its own static electricity,’’ Wendt says.

“So he was getting these zaps that were contorting his body. Every time. But he knew he had to keep going.

“And he said the last one was the worst one but he went about 18 times out there and brought them in. They had to get them in, check them out, debrief them, customs and everything was there. It was a giant quarantine station.

“The chopper was into the wind and the pilot must have been flying blind with the weather.

Westpac Rescue helicopter pilot Ian McFadden

“It would break for a little while, you would get a little bit of a reprieve and another cell would come in again. It really was difficult conditions for us, so I hate to think what it was like out there hanging above this ship and a slick deck and all that sort of thing.

“[The ship] was still pitching, even though it was stuck fast, it was still moving every time the waves hit it. Terrible conditions.’’

Veteran lifeguard Warren Smith and others jump on jet skis and into the washing machine of the boiling sea next to the ship, hoping no one would fall but patrolling just in case there is a need for a quick rescue.

After 90 minutes, the extraordinary rescue - which continues to be lauded as one of the great maritime operations - is complete.

Ramplin collapses on the sodden turf outside the surf club. Spent.

Nickisson tells people that if you can rate rescues with a difficulty of one to 10, “then this was definitely a 10’’.

No one is injured. Everyone is safe.

And even in such precarious times, there is still time for some humour.

“It was pretty slick,’’ Wendt says.

“Towards the end of it, quite a few of these [Filipino seamen] were run past the media and were shepherded into the club, and one of the radio blokes yelled out to one of the seaman coming up the ramp: ‘how are you feeling’’.

“And we all looked and thought how is he going to answer, he probably doesn’t even understand the question.

“But he stopped, and looked, and he went: ‘I okay. Captain f---ed’. And that was it. He took off inside.

“And we thought that has to be the headline but we will never be allowed to use it.’’

Whoever may or may not have been to blame is for another day, week and even month. There is still work to do.

AS the big red ship called Pasha Bulker was hogging the world’s attention after wedging itself onto Nobbys Beach, Bob and Linda Jones were obliviously heading back home to Clarence Town after an early morning doctor’s appointment.

Boliermaker Nigel Beeston was just as ignorant, working deep underground at Centennial Coal’s Myuna Colliery at Wangi Wangi.

And Wayne Bull was busy at his panel beating job at Lambton.

By the end of the weekend, and as the rain and wind subsided, the four of them – and an extended Central Coast family of five – would become forever linked as the heartbreaking faces of the devastating East Coast Low known as the Pasha Bulker storm.

Linda & Bob Jones.

“Every time you see the Pasha Bulker, you think about it,’’ Linda Jones’ sister Libby Herington tells Fairfax Media.

“It was the worst day of our lives.

“I don’t think people realise that there were lives lost that day.’’

Jadie Beeston, a young mother and wife of Nigel, adds: “I think people remember that weekend was just an exciting storm, you hear people remembering the Pasha Bulker, the cars and homes being flooded.

“But they are all replaceable.

“It should also be a time where we honour those who we lost.

“It is difficult for everyone. His parents. His sisters. You don’t get over it, you just learn to live with it.

“It is still as bad now as it was then. For everyone.’’

And Wayne Bull’s sister, Michelle Schmitzer, is even more passionate about the need to remember those lost.

“I don’t like the Pasha Bulker at all. I hate it,’’ she says.

“A ship’s captain is told to lift anchor and take a boat out to safety. He doesn’t. My brother is missing and he is on page three.’’

The painful memories are the same. The ache of loss never completely dissipates. And the levels come in waves.

Libby Herington remembers that her sister Linda didn’t always go with her husband to his doctor’s appointments.

No one will ever know why she decided on June 8, 2007.

But she did. The love of her life, whom she met while they both worked at Stockton Hospital, also had a love of the rural life. And the pair settled in beautiful Clarence Town.

“He was very clever with his hands, Bob, and he loved a drink,’’ Ms Herington says.

“Linda was quieter but had such a beautiful heart, she loved her family”.

The pair had been to the doctors and were heading home as the rain continued to bucket down.

It was 11.20am when they reached a small bridge on Clarence Town Road which spans Wallaroo Creek, between Glen Oak and their home town.

But the creek, borne in Columbey National Park before it gathers momentum into Stony Creek and then the mighty Williams River, was already swollen from the endless rain.

Bob stopped the couple’s four-wheel drive before the bridge and watched on as a truck successfully navigated through the rising floodwaters.

Fatefully, he decided to take it on – they were just a few kilometres from the safety and dryness of their own home.

Witnesses watched on as the four-wheel drive hits the bridge before the wall of water took control – and all before it.

A Westpac rescue helicopter was called from the Pasha Bulker rescue to help in the frantic search.

But the Joneses never stood a chance and would later be found just metres from the bridge. Still in their seatbelts. And, importantly for their families, still together.

“We couldn’t believe it,’’ Ms Herington says.

“Mum was devastated. I don’t think she ever got over it. I don’t think any of us did.”

A few hours later, Wayne Bull had finished his shift at Steve Koulis Smash Repairs on Griffiths Road at Lambton.

But his car had been playing up and the 46-year-old was worried he wouldn’t get home. He asked a workmate to follow him home to Adamstown in the business’ loan car.

Wayne, a father of two, got home safely and decided to jump into the Ford Festiva with his workmate to get him back to the shop. It was a decision which costs him his life.

Stormwater drains across the city had been overflowing for hours now. The sheer amount of water had taken its toll. And the one that ran along the old water course known as Styx Creek was one of them.

As the Festiva travelled over the rail overpass along Griffiths Road, the pair were unaware of what was just a few metres ahead of them.

It was 6pm and dark. The Festiva is caught in the floodwaters, and as Mr Bull attempted to flee, he was washed away.

His mate never saw him and yelled for help.

Just like the Joneses, the father of two never stood a chance. His body was recovered several kilometres away towards Throsby Creek.

“The ferocity of the water coming down that drain was extraordinary and as Wayne opened the door he just got dragged out,’’ sister Michelle Schmitzer says.

“We miss him terribly. He was just a good egg. I am not just saying that because he was my brother. He was a great bloke and we want people to remember him for his smile, not what happened to him.’’

That Friday night, Nigel Beeston got home to Heddon Greta safely after spending hours travelling along battered roads.

He was a hard worker, the family’s breadwinner, and he didn’t shirk an overtime shift the following day, despite the weather.

He finished that shift about 4.30pm. It was Saturday afternoon and, again he was struggling to find his way through the maze of flooded roads. He rang his wife again at 6pm.

“He said it was slow going but he was going through Freemans Waterhole and he was only 10 minutes away,’’ Jadie Beeston says.

“But he never made it home.’’

As he travelled along Leggetts Drive near Brunkerville, a roadside tree succumbed to days of its roots being undermined by rainwater. It fell and crushed Nigel’s utility cab.

Jadie, who was waiting for Nigel to get home to her and their five-year-old Skyla, received a call from his grandmother.

Nigel Beeston with his wife Jadie and daughter Skyla

“His nan rang and asked who was driving the ute and I said it was Nigel. When she couldn’t speak I knew something was terribly wrong,’’ Jadie says.

“I kept ringing his phone constantly trying to contact him. But I obviously couldn’t. I said it couldn’t be right, I had just spoken to him. But it was.’’

If they were to allow fate to enter their nightmares, the families of those lost during that storm weekend could be lost in grief.

The Joneses could have waited. Wayne Bull could have stayed home. And Nigel Beeston was a split second from safety.

“It is a moment that constantly goes through my head,’’ Jadie Beeston says.

“If he was driving one kilometre faster or two kilometres slower. It was the worst luck and timing possible. There are so many things he could have done and he would still be with us. Stopping and tying his shoelace. Anything.’’

JUNE is the hardest month for Jim and Helen Bragg, when Palmdale lawn cemetery on the Central Coast becomes “our second home”.

Their daughter Roslyn, 29, her partner Adam Holt, 30, their two granddaughters Madison, 3, and Jasmine, 2, and their daughter Sharon’s son Travis, 9, died when a section of the Old Pacific Highway collapsed during the Pasha Bulker storm on June 8, 2007 and the five were swept away in the raging floodwaters of Piles Creek.

Mr and Mrs Bragg visit Palmdale each year on the anniversary. They go to Palmdale again on Roslyn’s birthday, June 23, and on the birthday of their baby son, James, who was a cot death baby at three months old, many years ago, and also in June.

“June is not a good month, but no month is a good month when five members of your family die. It never leaves you, ever,” Mrs Bragg said.

“There’s always birthdays and anniversaries and holidays when you’re reminded of what you’ve lost, so we go to Palmdale.”

Mr and Mrs Bragg travel to Somersby regularly to visit a memorial near the bridge that was built after the tragic events of that night nearly 10 years ago, and named the Bragg-Holt bridge after the family that was lost.

They take a lawnmower and whipper snipper to care for the memorial, weep at times, and renew the anger they feel towards Gosford City Council – now the amalgamated Central Coast Council – which an inquest found was largely responsible for the road’s collapse.

The council’s failure to care for the memorial is indicative of the council’s response to the tragedy, Mr and Mrs Bragg said.

“We still can’t believe no one was prosecuted or lost their job at the council because of what happened,” Mrs Bragg said.

“We live with a lot of hate for people who didn’t do the right thing. You’d think they could mow the grass around the memorial and make sure the weeds don’t come up but that seems to be beyond them. It’s in the past for them. We’ve got to live with what happened every minute of the day.”

Mr Bragg wept as he remembered the hours that passed on June 8, 2007 after Roslyn and her daughters dropped in to the Darrell Lea store in Gosford that her parents owned. The long weekend storm that eventually claimed nine Hunter and Central Coast lives was already wild on that Friday afternoon.

“Roslyn said she was going to our daughter Sharon’s house and she also had to take Adam to work at Somersby,” Mr Bragg said.

A few hours later, and after the storm dramatically increased in intensity, Mr and Mrs Bragg grew alarmed when they could not contact Roslyn or Adam.

Roslyn Bragg and partner Adam Holt, with their children Madison, 3 and Jasmine, 2

They went to their daughter’s house, they rang friends, family members, police and local hospitals, and several times went to The Entrance police station for news.

It was at the police station that they learnt of the Old Pacific Highway collapse at Somersby, near where Adam Holt worked.

“As soon as we walked in and said our name about six coppers looked up with funny looks on their faces and we just knew,” Mr Bragg said.

The memory reduced him to tears.

“The tears are never far away, and especially now,” Mrs Bragg said.

“We can’t believe it’s been 10 years.”

At an inquest in 2008 into the Old Pacific Highway collapse NSW Deputy State Coroner Paul MacMahon said the deaths of Roslyn Bragg, Adam Holt and the three children was an “unnecessary” tragedy.

He criticised the council, and compared its failure to act on warnings about the road with the Sergeant Schultz character on the 1960s television show Hogan’s Heroes, “whose defence to everything was ‘I know nothing’.”

“It must have been apparent, even to a layperson but especially to a qualified engineer, that the loss of the structural integrity of the culvert pipes due to rusting and the continual washing away of material from the area of the culvert would at some time lead to its collapse,” Mr MacMahon said.

Mr and Mrs Bragg sold their business in the immediate aftermath of the storm and the deaths.

“The council’s incompetence basically destroyed a lot of people’s lives,” Mr Bragg said.

They take comfort from the support they continue to receive from the community. The Entrance Bateau Bay Football Club, where Travis Bragg was a player, presents a trophy each year in his honour.

Travis Bragg.

“Sharon says a few words each year until she starts crying,” Mrs Bragg said.

Mr Bragg takes a single rose to a beautiful area at Palmdale where there are plaques for his daughter, her family and his other daughter’s son, and heartbreaking photos of five lost young lives.

He places the rose beside the plaque where his daughter is forever smiling.

“He always called Roslyn his rose when she was alive,” Mrs Bragg said.

The extended Bragg family will leave the Central Coast for the 10th anniversary of the Pasha Bulker storm and gather at a location in the Hunter.

“It’s very hard to talk about it,” Mr Bragg said.

“The pain of what happened confronts you every day. There’s photos on the walls. There’s significant dates. Others can forget. We can never forget.”

IT is 9.37pm on July 2, 2007, some 24 days since her grand, if not unwelcome arrival, and the temperature is about as cold as the stares. The Pasha Bulker’s pig-headedness appears to have dashed another attempt to pull her free.

Then NSW Ports Minister Joe Tripodi and Newcastle Port Corporation chief executive officer Gary Webb are halfway through a press conference on Fort Scratchley, high above the deserted Nobbys beach on this Monday evening.

And then, one of the cameramen notices something behind the men. Hold on a second. Is that light supposed to be moving.

“We had come to a point where, you know what, she has turned fully but she just didn’t want to let go,’’ Mr Webb recalls.

“So we were again in a tone of transparency saying ‘well, it mightn’t be tonight, but there will be another time’.

“And suddenly my phone was going bananas and I suspected that behind me the ship was wanting to move. So the incident control centre was letting me know. But I couldn’t look at my phone.

“Suddenly the media guys said ‘will you get out of the way, it’s moving’.’’

After all this time, after all the theories about how wedged the Pasha Bulker was into the reef and whether it would become another Sygna, the big 40,000-tonne girl decided to leave without fuss.

No crunching of steel or grinding on the rock. No more monster whip-cracking from cables snapping. Nope, she had turned on her heels and was out of there.

Even high on the hill where guns once peppered Japanese submarines, and despite a one-kilometre exclusion zone allowing this moment to only be witnessed by a lucky and chosen few, there were euphoric scenes.

There were cheers and pats on the back. Minister Tripodi even threatened to do an Irish jig. Those present have promised he didn’t.

“I enjoyed the drive home that night but even then I was very aware of what the next steps were going to be,’’ Mr Webb says.

“Because you have a dead ship that needs to come in to port, so clearly your mind moves to that very quickly, you can’t get too euphoric for too long.’’

And there was also no euphoria on board the Pasha Bulker.

Salvage master Drew Shannon, working for Svitzer, remembers the moment like yesterday.

“I was on the bridge and she just squatted back down a bit in the water and off she went,’’ Mr Shannon said.

“There was a huge wave of relief but believe me, that is some of the most critical times.

“You take the ship off the rocks where she was steady and back into the water. Is there another hole we don’t know of. Is there a leak. The next 24 hours was crucial.

“I didn’t breathe a sigh of relief until we were back in the harbour.’’

That mindset of always looking towards the next challenge appears as a common denominator throughout the salvage – even since the moment the Pasha Bulker crashed onto the beach.

In fact, back on the morning the Pasha Bulker hit the sand and reef, and as word was still emanating through the gale-force winds, authorities had turned their attention to other dangers.

Gary Webb was in Melbourne at a ports conference when he got the first call about the Pasha getting close. And when it was confirmed that it had beached, there was no time to worry about it. Webb headed home as the situation worsened.

There were at least two other bulk carriers which were threatening to hit Hunter beaches, including the Sea Confidence in Stockton Bight.

“The Pasha wasn’t going anywhere,’’ Mr Webb says.

“We would come back to her. But it was the other two that occupied most of our focus on that Friday afternoon whilst we set up the response centre.’’

He later adds: “I’m not trying to overplay it, but it is well on the record and your records show those two vessels being a risk.

“So that is really where we were the first night, establishing the incident control centre for the Pasha and working out what happens if.

“We were always hopeful at worst it might be one other, at two it would have really have stretched our resources and we would have had to really have changed our thinking a bit.’’

There was also a few other things happening too. Like flooding. Like the expected silt to hit the harbour needing dredging. The harbour was obviously closed. Not that it mattered too much because a rail line used to transport coal to the harbour had also been washed away.

But no one else really cared. The attention was on the big red ship on Nobbys. And how they were going to get it off.

And there was a lot of advice being sent to authorities. Some good, some not so good.

“Sometimes the incident control centre would say to me we have been given some free advice today from the general public,’’ Mr Webb says.

“So I would say pick your favourite for the day. Someone thought we should put kites on the ship and help it fly away. Something thought we should dredge a channel through Macquarie Pier onto the main channel. Someone wanted the 50 ships to come back and put the anchors on there and drag it off.’’

Enter salvage master Drew Shannon and his crew. Again. They needed to find out what damage had been done to the Pasha before they could even think about how to pull it off.

In their industry’s terms, was the damage fatal or not.

And that took days of watching how the Pasha behaved in different tides with the bow on the sand and the stern on the rocks.

Those characteristics were looked at by a naval architect, who then had his opinions “peer reviewed” by others across the world. Three or four days in, and this had become a 24/7 operation.

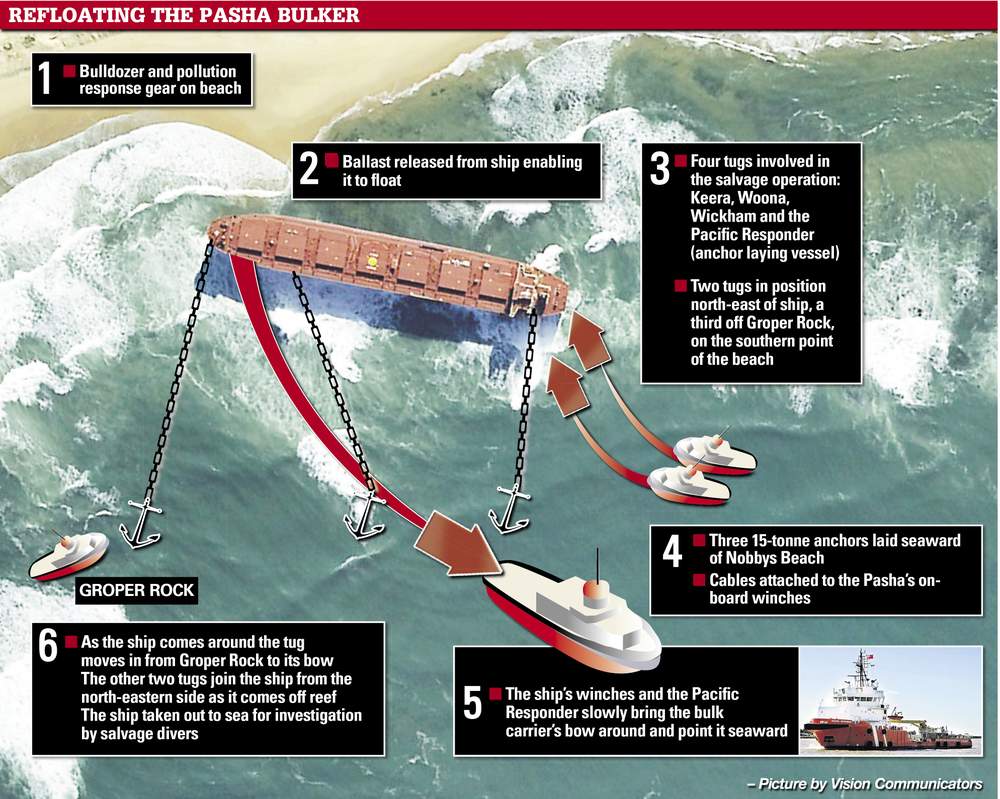

Once it was confirmed that the Pasha was not dead, the logistics really hit. They needed the massive tugs, the 15-tonne anchors to be laid seaward and the 450-metre long cables which the Pasha would use to help pull herself free.

In the meantime, Mr Webb had decided there needed to be a one-kilometre exclusion zone during the salvage operations.

Some critics suggested it was because the port corporation didn’t want people to see them fail.

“[Our thoughts were] what happens if something does go wrong. Or what happens if someone gets excited and, in the dark, ends up down on the beach and something goes wrong,’’ Mr Webb says.

“We were not going to have someone killed so there is no doubt that when you have the lines underweight and remember the ships winches were working offthe anchors as well as the pull from the three tugs that were on it.’’

It would take three attempts over five nights to finally drag her free, with several cables snapping as the window of opportunity – including high tides – was getting narrower and narrower.

“Mother Nature did not play ball during the preparation and the night of the first attempt Mother Nature was cruel because the ship was moving quite violently {before a cable snapped],’’ Mr Shannon says.

And just like she had been throughout the ordeal, Mother Nature failed to help on the night of July 2, 2007, stubbornly deciding it was time to be calm when the salvors needed some swell.

But even without the help of Mother Nature, they won. The Pasha was free.

GLEN Ramplin wasn’t meant to be working on the day a chopper lowered him to the deck of the Pasha Bulker.

The Westpac rescue helicopter crewman, then 33, had swapped shifts so he could go to an antenatal class with his wife Amanda.

Their daughter Monique would be born about six weeks later at John Hunter Children’s Hospital.

But on June the eighth, 2007, when fate was still scattered in the storm, the service’s Bell 412 helicopter was diverted from the grounded ship at Nobbys beach to Clarence Town because local couple Bob and Linda Jones had been swept away. The Joneses wouldn’t survive.

By late morning the Bell had winched four of the ship’s 22 Filipino and Korean crewman to safety. The only way onto dry land for the remaining 18 men was aboard the smaller BK 117 chopper of Westpac Two.

Another ship was threatening to ground at Stockton, and another near Redhead.

It felt to the rescuers as if their mission, in cyclonic gusts and gunshot waves that licked up the sides of the bulk carrier, was being spread thinner by the minute.

“I’d sort of envisaged it was only going to take half an hour. In the end, it left me on the deck having to get 18 crewmen off,” Mr Ramplin said.

“The wind was gusting up to over 100km. It made it really difficult for the pilot to manage his power, and every time I touched the deck the static discharged through me.”

Glen Ramplin dangles above the Pasha Bulker's deck. Picture: Darren Pateman

The noise of the blades grew whisper-thin in the storm, Mr Ramplin remembers, as his boots slid onto the deck.

The helicopter’s pilot, Mr McFadden, considered landing on the deck but decided against it. Social media was in its infancy, and local radio-primed onlookers huddled on the road beneath Fort Scratchley to watch the rescue unfold on their doorstep. Few had expected to see a ship this size.

Mr Ramplin touched down on the 40,000-tonne Pasha Bulker’s oily deck and fought the salt spray whip. The chopper funneled overhead, and he braced for a shock from its cable. But not this.

“It was like lightning came out of the hook. It knocked me flat on my backside. After that I let the hook touch the deck.”

One by one, Mr Ramplin wrangled, harnessed and lifted the ship’s fuel-soaked crewmen into the chopper. Some cried, prayed, and hugged their rescuers. Few spoke much English, but one later quipped to reporters that the captain was “f---ed”.

Eighteen times the static jolts ran through the deck and through Mr Ramplin, most violently on his final rescue of the captain.

Subsequent findings about the ship’s grounding didn’t read well for the ship’s South Korean master, who was exhausted from a lack of sleep, hadn’t ensured enough ballast on his ship, and was found to have taken an ill-timed breakfast.

“I didn’t see the captain until he was the last one we got off. I guess you could tell what had unfolded was weighing heavily on him,” Mr Ramplin said.

“We didn’t exactly have a conversation about it. I just told him, ‘time to go’.”

After two-and-a-half hours, the last man airlifted to the makeshift emergency centre of the Nobbys surf club was the captain.

Chief crewman Graham Nickisson – winchman throughout the rescue – said later he “really felt for him”.

“It was a pretty emotional business.”

Of all Glen Ramplin put himself through that day, his dry-retching in the Nobbys grass was private and brief. But it’s dry-retching he remembers.

“I get seasick real easy, and all the static shock had taken its toll on me.”

By June 8, 2007, Ben Donaldson was better-known as a gravel-voiced Merewether builder with a passing resemblance to Buzz Lightyear than as a Newcastle Knight who’d played nine games at dummy-half.

That morning Mr Donaldson, 28, was one of three jet ski operators who rode out with Newcastle’s head lifeguard Warren Smith asked to support the helicopter rescue mission on the Pasha Bulker.

The other two were Josh Ferris and Mr Smith’s son Rhys. They pushed their skis off from Carrington boat ramp and roared out through the billowing grey mouth of the harbour.

“My son said, ‘you're not going out there alone, dad’, so he and a couple of his mates came out with me,” Warren Smith recalled later.

They were to assess the damage to the ship’s vast red hull – “a bit of cracking, but not too dramatic” – and retrieve anyone who fell from the chopper or the deck. Their only shield from the wind and the 18-metre white tongues of water, Mr Donaldson said, was the mass of the Pasha Bulker.

“The tugboats were just getting engulfed. Because the waves were rollers it was nonstop, and for a while going out there we couldn’t see the Pasha Bulker,” Mr Donaldson said.

“When a gust of wind came through, that chopper was blown 20 metres like a pendulum.”

All day the radar image of the storm glowered over the Hunter “like a purple scroll”.

Night fell and Mr Donaldson went home to Frederick Street, as his neighbours’ yards sloshed under 160mm of rain and their cars bobbed and scraped against the kerb.

His place seemed clear of the floodwaters, so he slipped on a wetsuit pushed out into the canal of Frederick Street on his “Mal” surfboard, just so he could say he’d paddled down his street.

“Then people were asking me to get them out of their houses,” Mr Donaldson said.

“I did six or eight people on me Mal. An elderly lady asked me to get her out with her cats.”

He paddled from house to house, ferrying the elderly, shivering occupants to the higher ground of Helen Street.

The water was rising and cold by now, about 10 degrees, and he swapped his Mal for his jet ski; it meant he could putt back through the streets and collect the lady’s wary cats in their cages.

There came a scream.

Christina and Victor Wang were doctors from Western Australia who’d moved to Merewether with their little boys Ethan and Jeremiah, who was seven months old.

Christina was at home with Jeremiah that night. There was a moment at her kitchen sink when the water wouldn’t recede down the plughole. Outside the window, water brimmed over the back fence.

Victor Wang was stuck at work at John Hunter Hospital and growing quietly desperate to get home.

He’d picked up Ethan from childcare, but couldn’t get through to his wife.

“Trees were down everywhere. The mobile network was down. I had to go back to the hospital just to ring her. I was new to Newcastle and I kept getting lost on the roads,” Dr Wang said.

“So I rang my friend who was a few streets away.”

The Wangs’ family friend Jim Lai arrived in his four-wheel-drive to collect Christina and Jeremiah but the car, as so many that night, drove into water that was deceptively deep. The engine died and they began to float. Water gushed in and pushed inwards on the doors.

“By the time we realised we could be flooded in it was already happening,” Christina said.

“The car started filling up and we had to get out; the water was up to our shoulders and we needed help fast because the baby was frozen and couldn’t handle much more.”

When Mr Donaldson found them and wrenched open the doors, Christina was shoulder-deep and holding Jeremiah above her head. The baby was purple. He didn’t cry until they splashed into Mr Donaldson’s indoor heated pool, and then they waited on his couch in footy tracksuits until Victor and Ethan arrived.

The family has since moved back to Perth, and Jeremiah is ten years old.

Before the storm, Mr Donaldson had had terse dealings with Newcastle City Council about the requirement to build his house to withstand a once-in-a-century flood.

“But in hindsight, you probably have to give them that one.”

On the day of the storm Naomi Roskell-West was 29 and increasingly aware of the rain that was blasting through Hamilton.

Her boss had left early to pick up her kids and Ms Roskell-West, of Valentine, decided to close up and collect her own three-year-old son, Zac, from his grandparents.

“I was a single mum. This was the Friday of my first week in a new job working in the office of a distribution company,” she said.

“I had to take a detour towards the stadium and I couldn’t believe how flooded it was. In the traffic near the service station on St James Road I thought, this is a bit scary. I decided I was going to pull up in front of a bowser and stay there listening to updates on ABC radio.”

Then she saw the cars being washed down the road and the quivering people between them.

It’s a struggle to explain, and Ms Roskell-West puts it down to being “analytical”, but she still feels anger towards some of them.

Ms Roskell-West, an office worker who’d “never been in the SES, Scouts, or anything like that”, climbed the bull bar of a four-wheel-drive to reach a man clinging to a car’s side mirror.

“I reached out to grab him before he could move away any further,” she said.

“I can’t imagine what this guy must’ve been thinking, with this chick coming up at him on the front of a four-wheel-drive.”

On higher ground, the service station attendant decided it was time to close – but a woman and three children were still huddled on the roof of a car.

“All I could see was this water pounding on the front of their car. I screamed bloody murder, told [the attendant] ‘you are going to get these people killed’.”

The servo doors slid open. Ms Roskell-West found a ball of fine rope on a shelf and tied a length around her waist. Shaky and numb, she told herself to tie a proper knot. She tied the other end to a light pole and fought the chest-deep surge.

Unseen objects brushed her legs. The only permissible thoughts were “keep going” and “don’t slip”. She hasn’t seen the woman or children since she held their hands in that cold water, but she’d like to.

Not, she adds, because of nostalgia.

“I don’t see it as a positive outcome. I mean, it is, because those people are OK, but I think it’s quite sad,” Ms Roskell-West said.

“It’s a massive reminder that Mother Nature holds all the cards.”

Instead, she says it’s complicated. The days after the storm were “very much a reality check”.

Ms Roskell-West and Zac were evacuated to a hall around the corner from their house in Valentine and given blankets and soup. She still wraps herself in one of those blankets.

Later that night the police were ferrying people to Wests. She called her whole family and told them she was OK.

In the weeks that followed, the Hunter gradually realised that a series of brave interventions had stopped the death toll from climbing into the dozens.

Cardiff was a microcosm of the heroics; as staff from the suburb’s vet surgery carried a German shepherd with a broken back through the storm, five locals put down their beers to help rescue 80-year-old Pauline Eichman from her flooded home.

The five mates tethered themselves to the Lemon Grove Hotel and helped paramedics Al Qvist and Scott Hardes carry their elderly patient to an ambulance.

“The bystanders made a huge difference,” Mr Hardes said, echoing a tale told across the Hunter.

Thursday’s 10th anniversary of the storm, for Glen Ramplin, will be overshadowed by the realisation his daughter is nearly a decade old. He doesn’t think about the Pasha Bulker much, but says helicopter crewmen think about things like the significance of a shift swap.

The June long weekend is saturated in history for Ben Donaldson, who celebrates his wedding anniversary and the birthday of daughter Saoirse.

For years, Naomi Roskell-West couldn’t drive past the BP on St James Road.

“At one point I was painfully affected by it all,” she said.

“Then one day, without even realising it, I’d done it. Now it’s just a heaviness in the pit of my stomach.”

And she still gets nervous about the forecast of an East Coast Low.

TEN years on, the popular narrative of the Pasha Bulker’s grounding on Nobbys beach is that the master of the ship was solely to blame for the events of that tumultuous morning.

And yes, the two official reports into the events of Friday, June 8, 2007, do lay the blame fairly and squarely on the South Korean in charge of the vessel.

But read the reports together and it becomes evident that other factors were at play.

The first report, of 60 pages, was handed down by a state government authority, NSW Maritime, on December 5, 2007. The second report, of 90 pages, was released by a federal agency, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, on May 23, 2008. Both make fairly similar appraisals of how the Pasha Bulker got into trouble but they differ substantially in their appraisal of the role of Newcastle Port Corporation (NPC) and of its maritime communications arm, the Newcastle Vessel Traffic Information Centre (VTIC).

ATSB executive director Peter Foley releases the bureau's final report in 2008.

With one exception, the state report gives NPC a clean bill of health, saying it “responded to the emergency in a very competent manner, exercising appropriate control and integrating with the other emergency services involved”.

It found that “verbal communications provided by NPC at the time of the incident were adequate within the existing framework”.

The exception covered a crucial area.

The state report notes that NPC’s safety capability, as recognised through its Port Safety Operating Licence, had been given a clean bill of health a day before the Pasha Bulker grounding by a subsidiary of the shipping insurer Lloyds.

After the grounding, investigators went to get the recordings that are automatically made of all communications between VTIC and the various vessels, only to find “the associated recording equipment was, however, not working [on the day of the grounding] and had not been operating since June 5”.

“This was not known to the VTIC operators, the report continues, adding with masterful understatement, that: “The availability of this data would have been helpful to this investigation”.

Although the federal report still puts the overall responsibility firmly on the shoulders of the Pasha Bulker’s master, it lists a series of areas in which NPC could have done better on the day.

Indeed, nine of the report’s 11 recommendations covered “safety issues” for NPC “to address”.

It says: “Even with the resources available to NPC, including the collective local knowledge of the harbour master and pilots and the weather monitoring equipment at VTIC, the port corporation was not sufficiently responsive to the increasing seriousness of the situation that developed from the evening of June 7.”

“By the early hours of June 8, a dangerous situation had already developed but it appears not to have been recognised until the corporation’s ‘incident control system’ was activated at about 8.30am.

After this time, the situation was more closely monitored and weather advisories were provided. Consequently, the masters of those ships that were relying on guidance from VTIC probably did not assess the risks appropriately and eventually were surprised by the severity of the weather.”

Although the full submission by the port corporation to the federal investigators was not released publicly, two excerpts included in the report quote the port corporation as saying it “does not accept” that its communications that day “would create any confusion” or have “adversely influenced the decisions of” any of any (ship’s) masters”.

(For the record, the Pasha Bulker’s owners also rejected the federal report and its findings as not “valid”, although the investigators say the owners did not provide any “evidence or argument” in support.)

But the biggest difference between the two reports lies in their treatment of what happened after the Pasha Bulker lifted its anchor, at about 6.30am.

The state report says that between 7.20am and 9.30am the Pasha Bulker was told at least five times that it “ appeared to be dragging its anchor or drifting into the restricted zone, within two nautical miles, or 3.7 kilometres of the coast”.

That was the only mention of the “restricted zone” in the state report, and it was not until the federal report was issued five months later that its importance became clear.

As the federal report notes, the purpose of “restricted area” (its formal name, rather than “zone”) is to “keep the [harbour] entrance clear for ships entering or leaving port”. The federal report found that three vessels, Santa Isabel, Sea Confidence and Pasha Bulker, were tracking north when VTIC told them they should not enter the restricted area.

“Given that all three ships were struggling to clear the coast and that there was no need to keep the area clear because there was no traffic into or out of the port, these communications were of no benefit and unnecessary, and may also have adversely influenced the decisions of masters, including Pasha Bulker’s,” the report says.

This is the crucial question. Look at the track of the Pasha Bulker and you see the vessel heading out to sea until 9.06am, when what both investigations describe as a badly executed turn began the vessel’s hour-long journey onto the shore at Nobbys.

The federal report again: “The communication by VTIC at 9.10am asking for Santa Isabel to leave the restricted area and two minutes later for Pasha Bulker to also do so probably had some influence on the subsequent decisions of their masters, even though it could not be ascertained exactly what action they took and when they took it.

“Other masters in the area may at least have been distracted by these communications. In any case, given the difficult circumstances and the precarious situations some ships, including Pasha Bulker, were in, such unnecessary and irrelevant communications by VTIC could only cause confusion and were therefore inappropriate.”

In another section, the federal report notes that just after 9am, the Pasha Bulker “helmsman brought the ship back to a heading of 140º and the wind was ahead”.

“Had this heading been maintained, Pasha Bulker would probably have cleared the coast in an easterly direction,” it says.

The day the federal report was released in 2008, I asked the head of the port corporation at the time, Gary Webb, whether the instruction to clear the restricted area had contributed to the demise of the Pasha Bulker. He said VTIC may have told the Pasha Bulker about the restricted area but it was "absolutely not" responsible for the way the master lost control.

Similarly, Australian Transport Safety Bureau team leader of marine investigations Michael Squires told me at the time that the bureau had "gone over and over" the path of the Pasha Bulker, especially the turn soon after 9am when it was inside the restricted area.

"We can't say that the master definitely turned because of the information from the [information centre] but we do say that the instruction was unnecessary, unhelpful, of no benefit and may have adversely influenced the decisions of the master of the Pasha Bulker and other vessels," Mr Squires said.

The MV Drake, formerly the Pasha Bulker.

If there’s a lasting legacy of the Pasha Bulker, it’s that it led to the creation of a new coal ship queuing system, where instead of the 57 ships that were anchored close into the coast back in 2007, waiting vessels now drift far out to sea, either east of Newcastle or up near New Guinea, as they wait their turn to load.

And the Pasha Bulker – repaired and refitted after the grounding and now known as the Drake – is still plying the coal trade, and was most recently in Newcastle in late March, taking a load to China.

If only ships could talk. And if only those tapes had been working...

IT is a rumour that has survived a decade that a TV producer asked the Newcastle Port Corporation if his network’s star duo could broadcast from the deck of the Pasha Bulker.

Breakfast personalities were instead parachuted into Nobbys for special editions with the stranded ship as backdrop, as the nation’s gaze fixed on the storm-battered second city of NSW.

Watching from the crowded shore in those bright, crisp days was Mitch Revs, a Merewether pop culture artist who was in his final year at Kotara High.

“I was probably getting through my exams, trying to get the day off school,” says Revs, who has produced two artworks depicting the Pasha Bulker.

“The attraction was just the size of the ship for most Novocastrians. Once I’d seen it I didn’t want to go back because you’d get stuck in that part of town.”

Revs has thought about it more since he was a teenager. Delving through media coverage of the salvage, he realised that Greenpeace had laser-projected onto the hull, “Coal causes climate chaos”. Revs was intrigued that such a detail could be lost in a decade. If a Pasha came to ground today, would it gain more or less traction with us?

“I think if it happened now, with the way social media has exploded, people would pinpoint these things,” he says.

“But it’s kind of a distant memory, to be honest. Being 17, I was probably more interested in what I was doing on the weekend.”

The collective thrill of the Pasha Bulker’s grounding, that dissipated into a kind of post-salvage hollowness, was explored by playwright Alana Valentine in Grounded, original title Tanker Town.

CAPTURING A CITY: Alana Valentine (standing right) with a Tantrum Theatre cast during rehearsals of her Newcastle-set play, Grounded, in 2012. Picture: Ryan Osland

In Valentine’s Newcastle the protagonist is Farrah Martin, a 15-year-old who wants to be a marine pilot.

Farrah is conflicted about her hometown in ways familiar to Newcastle teens – “I really like it here . . . but I would like to get away” – though unlike her fictional peers, she notices its harbour.

“I came to Newcastle in 2011 looking for a story I felt there was still a lot of interest in,” says Sydney-based Valentine, who won three Australian Writers Guild Awards for Grounded including best script.

“One thing I noticed was that a Thai takeaway had a giant picture of Nobbys beach with the Pasha Bulker, stranded.”

Valetine spent two months doing interviews in Newcastle before writing what was dubbed her “Australian Billy Elliot”.

She was flown by helicopter over rough seas onto a Panamax class bulk carrier. How many people, she wondered, even noticed the port before that day in June? Her subjects ranged from marine pilot Sandra Risk to the people she met at bus stops; everyone seemed to have story.

The playwright that concluded the Pasha storm and grounding had lodged under the city’s skin, but that it had a hard time explaining why.

“For me, the Pasha Bulker story has a wonderful way of distilling Newcastle’s guts and grit,” Valentine says.

“The day they brought it limping through the heads . . . I wouldn’t call it pride, but it was this moment where the city went on. The grounding brought into sharp focus the fact that Newcastle is a port city. I guess it penetrated so many parts of people’s lives.”

Notwithstanding the fact that nine people had died, many in the Hunter picked the grit and glass from their wounds and entered three weeks of heady, flinty pride.

“Our generation’s Newcastle earthquake” became a rallying point, as a group of TAFE students produced Blame it on the Pasha Bulker (Bossa Nova) to be played on high rotation on local radio.

Two days after the storm, thirteen-and-a-half thousand people somehow turned up to Energy Australia Stadium to watch the Knights lose to the Tigers.

Pasha stubby holders became the “wish I’d thought of that” item of the season, and reporters’ questions were taken by TV newsreader-turned-MP Jodi McKay and Ports Minister Joe Tripodi without a hint of the toxic schism to come.

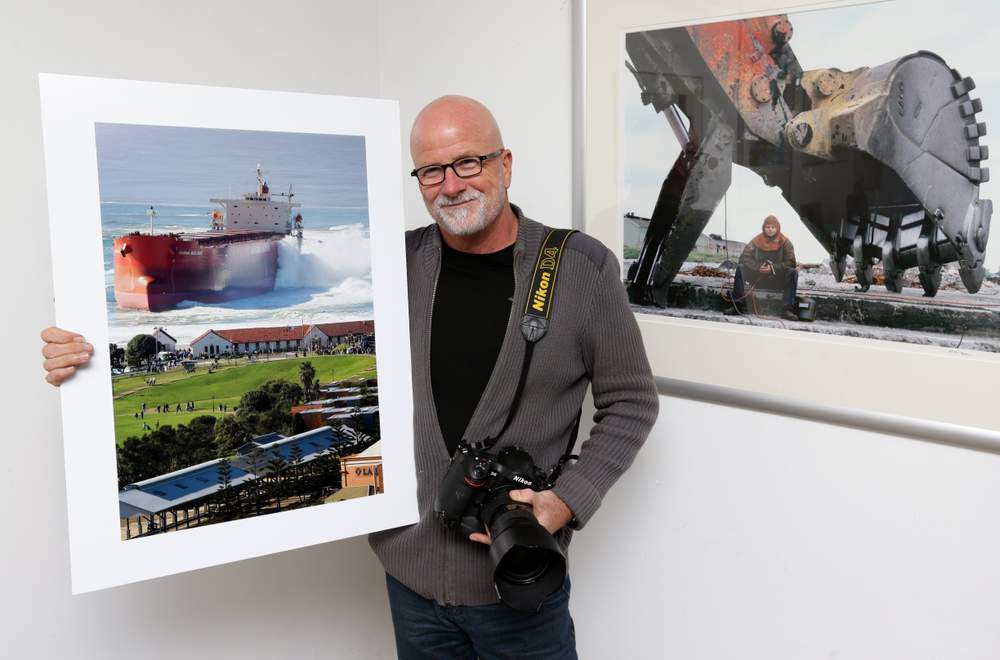

Murray McKean with his famed (and very real) photograph.

Buses brought sightseers from Sydney to Nobbys beach, and when locals bemoan the lack of a similar drawcard now, most are only half joking. For weeks, Newcastle had Sydney’s gridlock.

The pervasiveness of social media worked against Murray McKean, who climbed the tower of Christ Church Cathedral the morning after the grounding to take some of its most famous photos.

McKean’s image of the red monster bearing down on buildings and people is so unlikely it’s often deemed “fake”, and appears repeatedly in clickbait.

“I get frustrated,” McKean says.

“I’ve seen it used by car dealerships, it’s been on wine bottles, there’s a guy selling T-shirts at Charlestown Square, it’s won six photography competitions that I know of.”

The most recent was in Berlin.

Thoughts return to the storm’s victims, but more readily to abstract reflection. Bob Evans, né Kevin Mitchell of the Perth band Jebediah, released a single in 2009 titled Pasha Bulker. He told the Newcastle Herald he’d used pictures of the grounded ship to confront his feelings of being “lost at sea”.

It’s a feeling the Hunter confronts annually, with each forecast about a week into June.