DUSK, the summer of 1995, and word had got out – the new skatepark was being built at South Newcastle Beach.

The concrete had hardly been poured when Ben Cox, then 19 and already, as he is now, at 40, a semi-mythical godhead of Newcastle’s skateboarding fraternity, became one of the first to skate it.

The quarter-pipes that book-end the site today weren’t built. The half pipe wouldn’t exist for months. Instead, South Newcastle Skatepark was a sea of soon-to-erode hot mix and half-built modules.

It didn’t matter, they jumped a fence.

“From the moment you could skate it, that was it, we started skating it,” Cox tells Weekender.

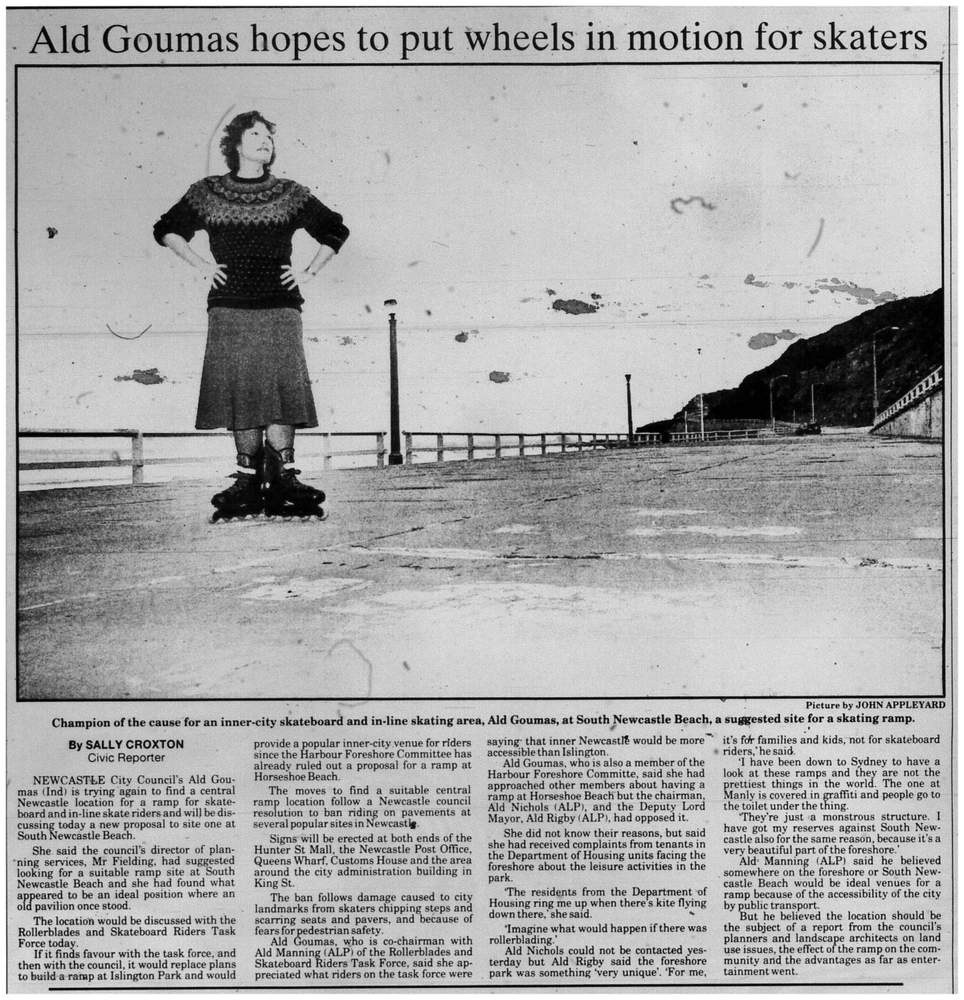

Ben Cox backside flip at South Newcastle in 1996. PICTURE: Aaron Brown

“All the transitions were built, all the curves, but there were no platforms or anything, so what we called the Volcano was kind of hectic because it was just two steep ramps with nothing in the middle.”

The Volcano – two quarter-pipes about two-and-a-half-feet high with, once it was completed, a one-and-half-metre flattop between them.

It’s one segment of a “Fun Box”, which, to the uninitiated, is a kind of universal skatepark component consisting, vaguely, of a box with a flattop and a ramp or rail on two or more sides.

Later, to transition from the Volcano, over the rail, and into the wedge – a smaller ramp on the other side – would be known as “the Onion”.

That was later, though.

“I just remember ollieing the thing, even that blew people out because of how steep those transitions were,” Cox says.

“There was this fear of if you don’t make it your trucks are gonna hang up, or worse, you’re gonna end up hanging off a sharp bit of concrete.”

Ben Cox, circa 1997, from Loves Ugly Children. Video courtesy of Amnesia Skateboards.

In the early 1990s, Newcastle, like the rest of Australia, started to worry about skateboarders.

Throughout the ’80s, skating, and skaters, had remained mostly invisible, using home-made ramps in backyards like the one in Ridge Street, Merewether.

But as the focus shifted from “vert” – skating on ramps – to the street, the subculture began to attract the unwanted attention of mainstream society.

In 1991, the NSW government banned the use of “toy vehicles”, like skateboards, from public streets, and in Newcastle skaters became an eyesore, occasionally the subject of angry letters or condescending newspaper editorials.

“I remember a story about skating doing damage to the Post Office steps,” says Marcus Westbury, the founder of Renew Newcastle.

“Which is ironic given what’s happened to the Post Office [and] how comparatively little damage skaters have done relative to the time, neglect and incompetence of just about everyone else.”

Before South Newcastle, skaters congregated at “Admin” – the council administration building in Wheeler Place – or “Stoves” – shorthand for the complex of abandoned factories behind Darby Street that were later developed into a gated housing estate.

Admin, though, was home.

“It was Mecca, our Embarcadero,” Chris Yeoh, 42, says.

Then Newcastle lord mayor John McNaughton with Ben Cox at 'Admin', circa 1994. Picture: Chris Yeoh

Yeoh grew up in Stockton and, in the early ’90s started a local skate zine called Amnesia, a seven-issue “scissors and glue” operation featuring Newcastle skaters that eventually morphed into a local skate company that sponsored people like Cox and Peter Schiffman.

He, like most other skaters of that generation, remember being “tolerated” at the spot.

“We killed those benches and ledges, like they were visibly ruined from there being like 30 people constantly skating them, but we never really got booted,” Brett Eberhard, 43, remembers.

“We were definitely a pain in the arse, but we were a tolerated pain in the arse.”

It didn’t last though.

In 1993 the council began to erect signs banning skating at places like Admin and the Post Office, and the uneasy alliance that existed between skateboarders and the council began to crack.

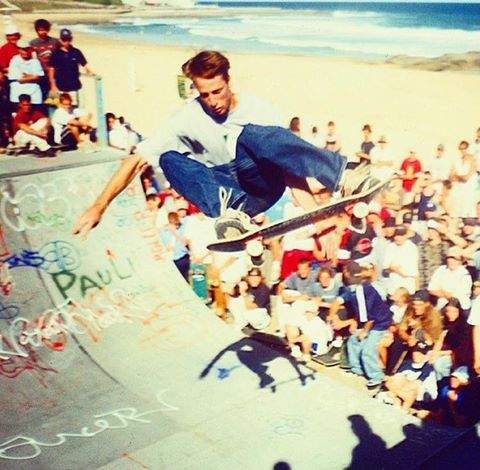

It was only the intervention of the late Margaret Goumas, then on the city council, who pushed for the park at South Newcastle to be built.

“To start with we in the Labor caucus weren’t all that fussed about building a skatepark,” the then mayor John McNaughton tells Weekender.

“But she convinced us by saying that we can hardly criticise these kids for doing something they enjoy and get considerable recreation out of if we don’t provide them somewhere to do it.”

Once it was built South Newcastle became, like Admin before it and Empire Park now, Mecca for a generation of skaters from right across the Hunter.

Haphazardly designed and immediately beset by salt, sand and wind, the park was never perfect. But for James Turvey, 34, that only added to its appeal, helping to breed a tougher, more versatile skater in Newcastle.

James Turvey, 34. PICTURE: Marina Neil

Only 12 when South Newcastle opened, Turvey, like Cox, remembers skating at the park before it finished, jamming street signs at the bottom of ramps because the joints weren’t installed.

“The park is hard to skate now but it was never easy, it eroded so quickly,” he says.

“Guys who were great skaters would come and be humbled all the time.

“It’s kind of an analogy for the skaters Newcastle produced.

“A lot of them were rougher than the guys from Sydney, but very adaptable.

“It seriously helped raise a generation of kids in Newcastle.”

By the late ‘90s, everyone knew something was wrong with Newcastle – the city hadn’t bounced back from the 1989 earthquake, and BHP was quietly abandoning ship.

As the Royal Newcastle Hospital faded away, South Newcastle became more remote, a situation only made worse in the 2000s when a giant boulder fell on Shortland Esplanade and no one could figure out how to move it.

“It was the most out of the way, derelict, kind of pseudo-junkie spot in the whole of Newcastle,” Ben Cox recalls.

“I remember when they were building it being told it was at South Newcastle and being like, ‘where?’”

But hidden away on a beach no one cared about, kids lined the seawall from morning to night; a human amphitheatre in which the city’s skate scene began to flourish.

Cox – already a sort of underground paragon – started appearing in national skate magazines. Amnesia was working on its first video – Loves Ugly Children – which featured the park heavily, and Tony Hawk himself visited in ‘96 and ‘99.

Tony Hawk skating the South Newcastle halfpipe as part of an ADIO demo in 1999. PICTURE: Kenny O'Brien

For some, like Ben Carnell, the park became a second home.

Now 37, for a period from the late ’90s to the mid-2000s, Carnell and his younger brother, Luke, seemed to possess an almost preternatural connection to the park.

“I was just there so often,” Carnell tells Weekender.

“I got used to every little crack in the ground, every bump in the bottom of the ramp.”

It could also be an intimidating scene.

Jason Campbell, 32. PICTURE: Marina Neil

Growing up in Anna Bay, Jason Campbell, 32, remembers the park as both a magnet and a source of menace.

“It was such a harsh place to come to,” he says.

“There was a very big alternative culture, a punk culture, and this sort of gritty rawness.

“More and more skating has become this family-friendly endeavour [but] that's definitely not how it started for me, it was a heavy scene and I liked that, that’s why I was attracted to it.”

Today, after two decades of being buffeted by salt and wind, South Newcastle is a rusty and eroded shadow of its former self.

In July last year Newcastle City Council announced plans to demolish and rebuild the park as part of its $36 million overhaul of the six kilometre stretch of coastline from Merewether to Nobbys.

Details of the council’s plan include the same landscaping and tiered-seating already in place in Merewether, and the initial design of a new skatepark includes a “competition standard” blue bowl on the sand that would sit alongside a gym.

“It’s a shithole,” 25-year-old local ripper April Caslick says of South Newcastle now.

“You look like you’ve been fed through a cheese grater or something when you try to ride there.”

Simon Lyddiard. Picture: Marina Neil

Newcastle’s skate culture has moved on, too. While South Newcastle’s street-inspired obstacles influenced a generation of skaters, the new locus – Empire Park – and its “gold bowl” have marked a broader shift in skating both in Newcastle and globally.

Simon Lyddiard was 11 when he first skated South Newcastle, and remembers it as being “always full of kind of sketchy characters, ‘graffers’, a lot drugged up weirdos”.

“But I love it and I know a lot of other people really, really love it for what it is,” he said.

“A lot of it is nostalgic, but it is fun and interesting and different to going to Croudace or Cardiff that are just pre-made blocks of shit.”

Now 28 and one of Newcastle’s sponsored skaters, he sees Empire Park as symbolic of something larger.

“Skating used to be something for people who didn’t fit in, part of a counter-culture sort of,” he says.

“Everyone’s debating the idea of skating in the Olympics, and to me and some other people Bar Beach is an example of that change.”

For Cox, too, the shift from subculture to competitive sport is hard to adjust to.

“I’m sure there are still cool people who skate Bar Beach and skate for tricks but it’s a really different vibe,” he says.

“To watch people training, I mean, at the end of the day anyone who rides a skateboard I feel a closeness to, it doesn’t matter to me, but it’s just a totally different reason.

“There was a turning point for me, going down to a competition in Sydney at the Hordern Pavilion in about 1997.

“By today’s standards it was nothing, but it was the first time I’d been exposed to that.

“I remember seeing a big Coca Cola sign and just the way it was run, the hierarchical structure of it, the way everyone was in their own little clique, I remember on that very day being like ‘nope, this is not what I’m into’.”