HAVING travelled half-way across the continent, Yanwyn Kirby trudges over the rain-softened earth under a swollen sky to catch up with his cousin, Les.

“He’s kind of like a mate, he’s definitely a cousin, but you think of him as a mate,” Kirby says.

The 59-year-old is walking through the Catholic section of the East Maitland Cemetery. He passes row upon row of departed souls until the mown grass surrenders to the unkempt border.

Here, in the last line of graves, Yanwyn Kirby finds his cousin. He may lie at the edge of the cemetery, but Les occupies the centre of Kirby’s thoughts.

That’s why he has journeyed all the way from his home in South Australia to visit Les’ grave.

“I have a great love for Les,” Kirby explains, as he gently brushes the stones on the grave.

“I’ve had a great love for Les since I was a very small boy. My father used to tell me stories about Les and also his brothers. And my grandmother was eight years old when Les used to visit family members.

"And if you got on to the subject of Les, she used to light up like a Christmas tree.

“He just feels very special to me.”

The inscription on the memorial says the first name was actually James, and his second name was Leslie. But Yanwyn Kirby knows him as Les. Everyone knew him as Les.

Les Darcy.

The granite cross marks more than where the remains of Les Darcy lie.

It is a monument to a champion boxer, a sporting hero. It is testament to a tragedy, a memorial for a life cut short at a time when millions of young lives were being lost in war.

And it is a symbol of how much Maitland admired Les Darcy, and how much the community thinks of him still.

That admiration is etched into the stone.

An inscription explains the memorial was erected by Darcy’s friends and admirers, “As a tribute to his unsurpassed brilliancy as a boxer; and in testimony of his high and loveable character. And of the uprightness and integrity of his life.”

The inscription ends with a quote from the Book of Wisdom: “Being made perfect, in a short space, he fulfilled a long time.”

Les Darcy wasn’t perfect. But in Maitland, many view him as close to it.

And 100 years after his death, Darcy’s short life of just 21 years transcends time.

IF a cemetery is the loneliest place on earth, then Les Darcy occupied the second loneliest: the boxing ring.

As boxers will tell you, once you have stepped through those ropes, it’s just you and your opponent, your abilities and your fears. It is literally stand or fall. And when you do fall, no one is there to help you back onto your feet.

“It’s not like a team sport, where you’ve got other guys who have your back; it’s one-on-one,” says former boxer and the trainer-manager at Maitland City Boxing, Barry McDonald.

“You question your ability, you wonder whether you’re good enough to beat the other bloke. It’s you or him.”

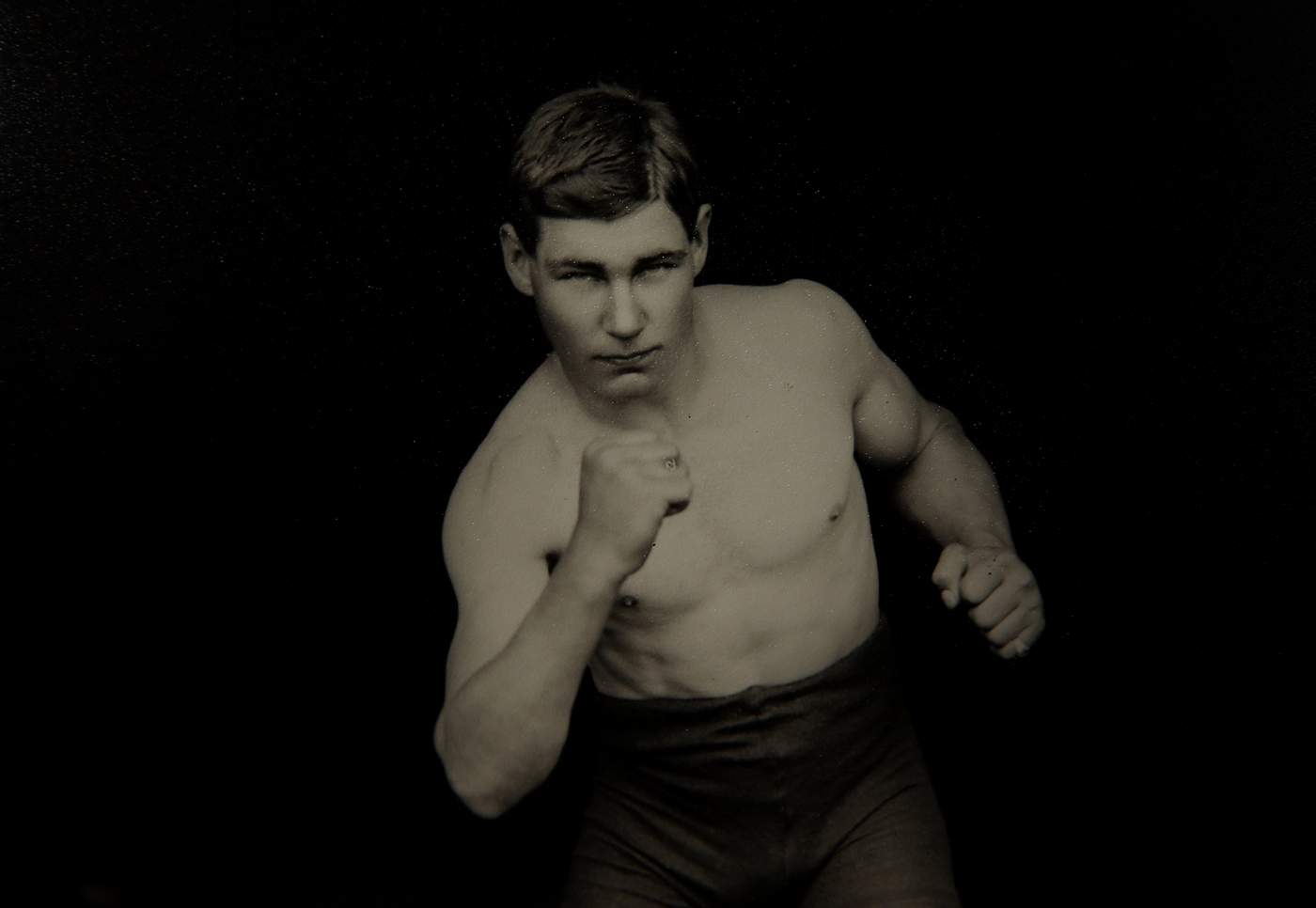

Les Darcy rarely fell. And more than stand, he soared in the ring. In at least 50 fights in Australia, he lost only four bouts, none by knockout.

“He was extraordinarily tough,” says Arnold Thomas, a boxing historian and past president of the Australian National Boxing Hall of Fame, which Darcy was inducted into in 2003.

“He was like a brick wall coming at you, and the brick wall was throwing non-stop punches.”

A KEY to understanding why Les Darcy was so good at boxing lies not only in a ring, but also in a paddock unfurling down to the Paterson River, just north of the village of Woodville.

The land is flourishing, the paddocks studded with a few trees. It was here, on a property called Stradbroke, that Darcy was born on October 28, 1895. A commemorative wattle grove was on the roadside for many years, marking the boxer’s birthplace, but it has gone.

Les was the second son of Edward and Margaret Darcy, a Catholic couple of Irish ancestry. The floods-fed soil along the Paterson River may be rich, but the Darcys were dirt poor.

Ned Darcy was a share farmer, a hard worker, but he developed a reputation for drinking too much. Yet the family kept growing. Les Darcy had nine siblings.

From a young age, Darcy felt a need to carry responsibility for his large family, to provide for them. He would learn how to do the carrying by curling his hands into fists. Les Darcy would fight for his loved ones.

“He was definitely a family person, his family were the centre of his world,” says Yanwyn Kirby. “He got into the boxing for his family.”

That opportunity came when the Darcys moved closer to Maitland. Young Les boxed in hard bare-knuckle bouts in makeshift venues around the town.

Initially, there was no money in it, but each fight brought him closer to earning a living. Each fight helped build him up physically. It also began building his legend.

The kid with the lightning fists and easy smile was grabbing attention in the Hunter, including the imagination of Mick Hawkins.

He is credited with giving Darcy his first formal boxing lessons, but, more importantly, they became good friends. Hawkins would become Darcy’s trainer and would stick with him through thick and thin, right to the end.

The desire to contribute financially had Darcy leaving school at 12 to work as a carter, before he was taken on as an apprentice to a blacksmith in East Maitland. These days, the site in Melbourne Street still tends to vehicles, only the motorised kind; it is a tyre-fitting workshop.

“He did shoes on horses, we do shoes on cars,” says Brad O’Neill, a member of the family who runs the business.

Brad O’Neill served his mechanic’s apprenticeship in the workshop and is chuffed that he works on the same site as Darcy did. While it is a different building to the one in Darcy’s day, O’Neill says the memory of Les the boxer still has a presence.

A commemorative plaque set into the front wall attracts tourists and stops passers-by.

“You see people pull up when they see the plaque out of the front,” O’Neill says. “They knew of him, but they never realised he was from Maitland.

“I think as a community we’re very proud of him.”

In the workshop’s office hangs a photo of Les Darcy shoeing a horse. What grabs your attention is that Darcy’s arm is as thick as the horse’s leg he is holding. His bicep is bursting out of his shirt, and virtually out of the image. Even in the blacksmith’s shop, while he was learning one trade, Darcy would continue to practise for the other.

Long-time Maitland resident Harold Mayo crouches and picks up an age-worn leather punching bag. He holds it gently and gazes at it admiringly, as if he is holding a jewel. Which in a way he is.

“This is what he would have trained with in the blacksmith’s shop,” Mayo says. “He would have hung it up and pummelled away at it for hours.”

At 90 years of age, Harold Mayo is too young to have ever met Les Darcy. But as a boy, Mayo would hear stories from his uncle about the boxer. They were roughly the same age and knew each other.

“He always said there’d never be another Les Darcy,” Mayo says of his uncle.

As a long-time president of the East Maitland Bowling Club, Harold Mayo ensured the memory of Les Darcy lives on. When he was approached by Darcy memorabilia devotee Robert Reid about housing his collection, Mayo helped organise a display area, a mini-museum, in the club.

As diners walk towards the club’s restaurant, they can look at hundreds of mementos, including the punching bag, photos, and tributes to Darcy. Harold Mayo says the physical reminders of Maitland’s devotion to Darcy have continued to make their way into the showcase, with donations by locals.

“Every barber shop in Maitland had a photo of Les Darcy and his achievements,” he explains.

“With all this memorabilia we have here, I’m sure his memory will live on into the future.”

Around Maitland and in Newcastle, the teenage Les Darcy was creating future memories. And he was beginning to make money.

In just one fight when he was 15, Darcy earned more money than he did in a week of working at the blacksmith’s shop. He apparently gave that money straight to his mother.

At the end of 1913, after a run of 17 wins, Darcy had his first loss to an older, more experienced boxer, Bob Whitelaw. But the 18-year-old was a quick learner. Three months later, he knocked out Whitelaw in a return bout.

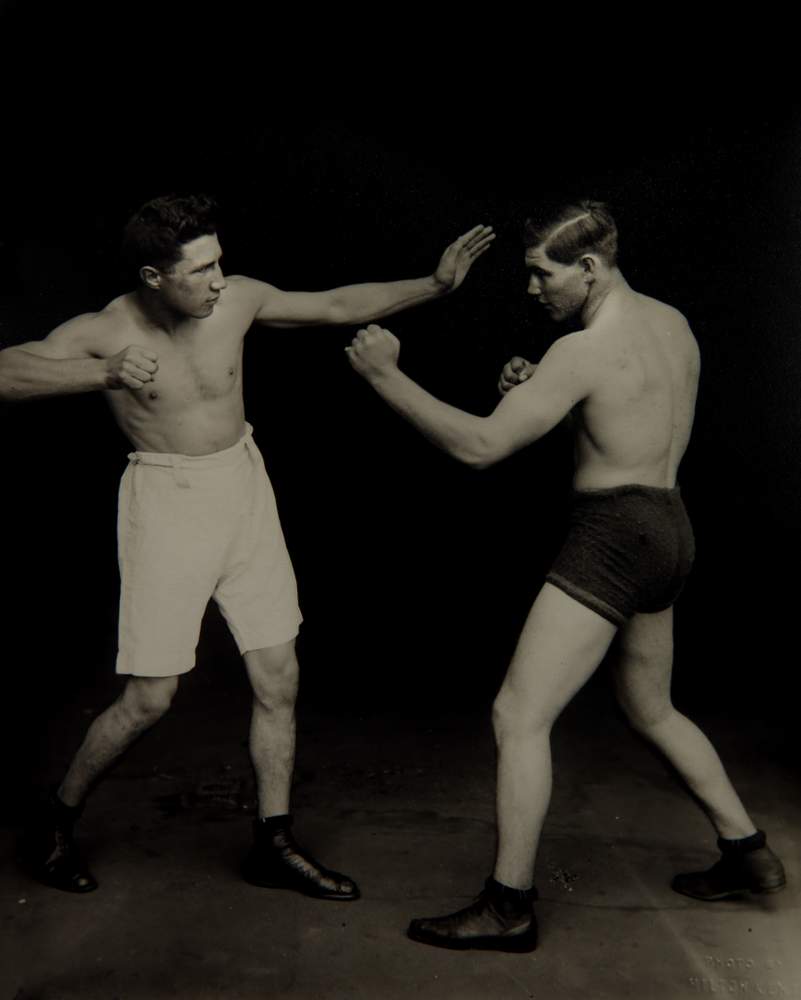

By then, Sydney promoters had heard about this kid from Maitland. Darcy was fighting in the Sydney Stadium against the best in the country and famous boxers from the United States, Britain and Europe.

“[Welsh boxer] Fred Dyer fought Darcy and said he was the best fighter, pound for pound, in the world,” boxing historian Arnold Thomas says.

“He was really quite elusive. He had an ability that put great fighters on the wrong foot, and he just seemed to be able to out-manoeuvre opponents. And he was just tough. My God, he was tough.”

Les Darcy grew from a local idol to a national champion. He held the Australian middleweight and heavyweight titles. When Darcy fought, the crowds flocked.

Train loads of supporters would head to Sydney from Maitland and the coalfields, while others took the overnight steamship out of Newcastle. Darcy was even cast in a film, as a hero. He had a fiancee in Sydney, Winifred O’Sullivan, and he was Australia’s sweetheart. But family remained Darcy’s focus.

“After every boxing match down in Sydney, he always caught the first transport he could home, until he bought his Buick car, then he’d drive home,” says Yanwyn Kirby. “Home is where his heart was.”

Darcy converted his heart, and his winnings, into bricks and mortar. In 1915, he bought a parcel of farmland in East Maitland and built a home on it. With his fists, Les Darcy had helped secure something better for his family’s future.

The house, Lesleigh, still stands in Emerald Street, and it is home to Jennifer Buffier and her family.

“He built this for his mother, so she had somewhere to live safely with all the family,” says Jennifer Buffier, after we meet in the front yard of the handsome brick house with a wraparound veranda.

“My understanding is that Les actually laboured on the job to help cut costs.”

She leads me around to the side of Lesleigh and points through the tangle of the garden to a door, which, curiously, has no steps leading to it.

“I’ve called it the door to nowhere,” explains Jennifer Buffier. “It’s an external door leading to Les Darcy’s bedroom. He would jump out to go train.”

He had built a home, but Les Darcy wanted more for his family. And he wanted to test himself in the world’s biggest cauldron for a boxer, the United States.

But this was 1916, and Australia was sliding ever deeper into the mire and slaughter of the Western Front during the First World War.

Young men were expected to fight, but not in the ring. Political pressure was mounting, including directly on Les Darcy to do his bit for the war effort.

He would serve, Darcy said, but first, he wanted to fight in the US.

What’s more, his mother was firmly opposed to her boy being on a battlefield.

Unable to get a passport, Darcy stowed away on a ship out of Newcastle.

Darcy’s secret departure drove a wedge only deeper into a nation already divided over the issue of conscription and military service.

The hero tumbled in the press, among boxing promoters who had made a lot of money out of him, and in the eyes of some Australians.

“He was called a coward, he was called a slacker, and a few other bad names,” says Yanwyn Kirby.

“He didn’t go away without giving it a great deal of thought. But he wanted to earn money for his family, because if he ended up in the trenches, he knew darn well, he probably wouldn’t come back, and if he did, he’d probably be crippled, or something. So he wanted to make sure they were set for life financially. That was the driving force behind it.”

Darcy stayed in touch with home. Maitland Regional Art Gallery has a Les Darcy collection of about 1000 items, including postcards he wrote from the US to his “Dearest Mum”.

They reveal a young man full of wonder at new experiences. In his neat handwriting, he tells his mother in a postcard from Pittsburgh that, “It’s not a very nice place, it’s just like Newcastle, only a lot biger [sic] … Love to all at home. Love Les.”

But the controversy of how he had left Australia followed him to the US. The Governor of New York State banned Darcy from boxing professionally.

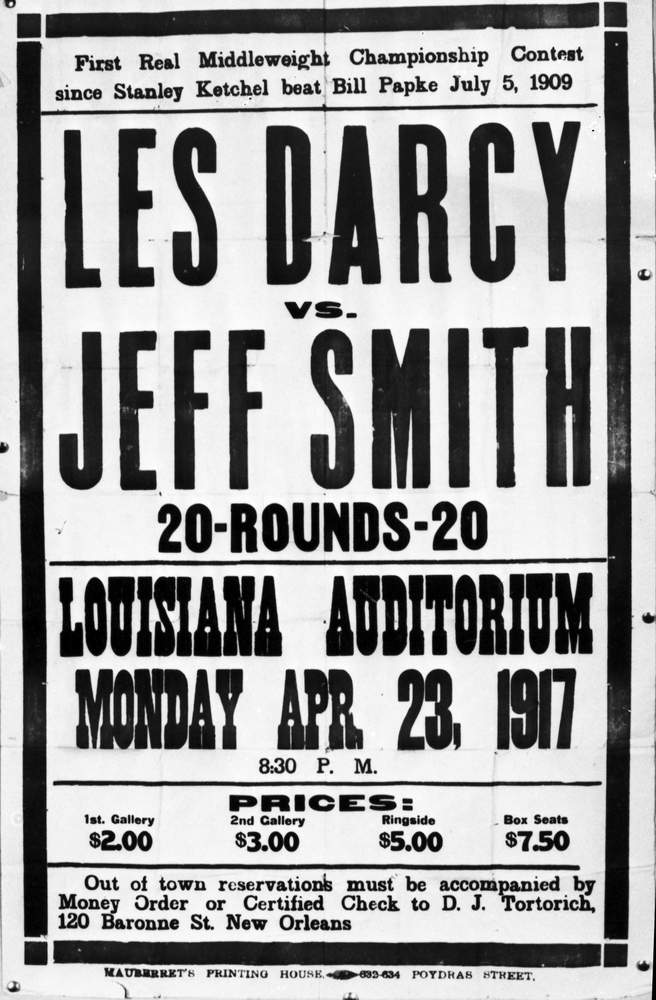

A letter in the Maitland Regional Art Gallery collection, written by Darcy from New York City’s Hotel Endicott (“Rooms, $1.00. With Bath, $1.50 & $2.00”), indicates his frustration: “somebody got to the Govoner [sic] and got him to stop me from appearing in New York State because I was a slacker, some dirty dog don’t know who anyhow. I have arranged to go out west and have a go and get started. I am matched to box George Chip on April the 19th in Clevland [sic] and May the 4th I go to New Orleans and box Jeff Smith and Tom Andrews wants us to box in Milwakee [sic] on May 20th so things are not so bad afterall … I am not downhearted too much about it because I have all the people with me….. Things will be alright when we get out west.”

But things would soon be not alright. Darcy developed an infection, apparently from the re-implanting of a tooth that had been knocked out in an earlier bout. Within weeks, the only fight he was engaged in was for his life.

Darcy was in Memphis, where he had been permitted to compete, when he fell ill. His friend and trainer Mick Hawkins was with him, and his sweetheart Winnie O’Sullivan, who was already in the US visiting a friend in Hollywood, dashed to Memphis.

She arrived just before Les Darcy died on May 24, 1917.

The American boxing great Jack Dempsey once told the author Ruth Park and her husband D’Arcy Niland that he thought Darcy “died of a broken heart”.

However, Darcy’s death certificate prepared by the State of Tennessee’s Department of Public Health lists the reasons as “streptococcus, septicemia, Septic endocarditis, and Lobar pneumonia”.

When news of Darcy’s death reached home, Australians were stunned. The man who had enthralled a nation, then divided a nation was now uniting a nation in grief.

“His death neutralised people’s antagonism towards him,” says Brigette Uren, the cultural director of Maitland Regional Art Gallery. “He became a symbol of lost hope. All these beautiful young men who died at at war.

"Les Darcy didn’t die at war, but he’s a shining example of one of our great sons who we lost overseas.”

In the United States, too, there was a profound sadness and, according to historian Arnold Thomas, a sense of guilt and shame on both sides of the Pacific.

“It’s as though Australians and Americans said, ‘What have we done to this kid?’,” he says.

In Memphis, there was a church service, which was packed. According to G. Wayne Dowdy, from the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library in Memphis, many in the city grieved over Darcy’s death, including the Mayor, who had befriended the young boxer.

“Darcy was a gentleman, every inch of him,” Mayor Thomas C. Ashcroft declared.

The casket, which had been paid for by a local sporting organisation, was transported to San Francisco, where there was another large service.

Then about 1000 mourners accompanied Les Darcy’s remains down to the wharves, to be shipped back to Australia, accompanied by his mate, Mick, and sweetheart, Winnie.

Once the casket arrived in Sydney, thousands paid their respects by attending a church service and participating in a procession to Central Station, for Les Darcy’s final journey home.

More than its residents being in mourning, Maitland was a town of mourning from the moment the casket was carried off the train on a winter’s night on June 28.

After a couple of days of services and ceaseless lines of people at Saint Joseph’s church in East Maitland, where Darcy used to attend Mass, the body was transported a few hundred metres away to the family home, Lesleigh.

The present-day owner Jennifer Buffier believes Darcy’s body was placed in the lounge room, a thought she finds “a bit eerie” whenever she is in there.

“It was viewed by people walking through the French doors, viewing the body, then exiting through the front door,” she explains. “Then the funeral left here on the Sunday to take him out to East Maitland Cemetery. To my knowledge, it was one of the biggest funerals outside of Sydney to this day.”

Crowds were packed around the home and along the route to the cemetery. The cortege went along Melbourne Street, taking Les through the landscape of his life, passing the blacksmith’s shop where he had worked and trained and the shops he knew so well.

Newspaper reports of the day estimated about 35,000 lined the route or attended the funeral.

“It was just a sea of people,” says Yanwyn Kirby. “They roped off the grave, just to give the family a bit of breathing space.”

As his remains were lowered into the ground, people wondered what Les Darcy might have done, what he could have been, had he lived longer. It is a thought that still courses through Maitland, 100 years on.

“He was only a young lad really and probably never developed his boxing skills to what they could have been before he died,” muses Jennifer Buffier.

“And it’s disappointing we don’t know whether he would have been world champion or not.”

But Harold Mayo says in local people’s minds, Les Darcy has been accorded that honour, anyway: “He’s looked upon in Maitland as the world champion.”

THE memory of Les Darcy remains in Maitland. Those reminders can be easily read, such as on the signs for Les Darcy Drive, which slices behind Lesleigh.

There is the statue of Les Darcy, moulded and erected in 2000 beside the East Maitland Bowling Club. As traffic whizzes by on the New England Highway, the image of Darcy is fixed in a boxing pose, as the world knew him, but with a serene look on his face.

That was Les, says Harold Mayo, who was instrumental in having the statue erected.

Mayo reckons the statue’s placement is also a tribute to Les Darcy.

“He would have walked past here many times, going to work, to church, and back to his home,” Mayo says. “I look upon Darcy as being an ideal person.”

There are the artefacts and keepsakes in public collections. The art gallery has a pair of Darcy’s training gloves, along with items that provide insights into a gentle and thoughtful character: a small delicate prayer book that Darcy carried, and a gleaming watch he had been given by friend and fellow boxer Dave Smith, with the inscription, “As a memento of his brilliant victory over Eddie McGoorty, 31st July, 1915”. In the collection there is also a violin that Darcy played. It is hard to reconcile that the hands that smashed into opponents’ faces also cradled this instrument to tease out melodies. The sum of these items, Brigette Uren believes, helps explain why Les Darcy is still loved and admired in Maitland.

Darcy’s legacy also continues in ways that can’t be seen but felt in the city. His character and influence flow through Maitland, shaping how it sees itself, as surely and as insistently as the Hunter River does. However, unlike the Hunter, Darcy’s effect on the town is never destructive.

“He represents everything that is good about Maitland,” Ms Uren says.

Darcy’s fighting spirit inspires others who step into the ring. At Maitland City Boxing, Jesse Catt is sparring with his trainer, Barry McDonald.

As the whip-crack of the gloves ploughing into the pads ricochets around the gym, McDonald quietly instructs the 22-year-old. On the wall behind, silently watching the pair training, is another instructor. It is a poster of Les Darcy.

“To me, he represents one of the toughest fighters ever seen in Australia,” Jesse Catt says, sweat streaking down his face.

Catt has had 23 amateur fights, winning 13. I ask how he thinks he would go against Les Darcy, if he were still alive.

“I don’t think I’d last a round,” Catt replies. “He’s got big punches, and he’d just push you around a bit, I reckon.”

“Does he still mean something in Maitland, to Maitland people,?” I ask.

Jesse Catt’s face hardens. I expect the sweat to stop running.

“Of course, he does,” he answers. “He’s a legend. One of the best fighters Australia will ever see, let alone Maitland.”

BACK at the cemetery, standing before the memorial to Les Darcy, Yanwyn Kirby is ensuring all is neat and tidy before he leaves.

Les, Kirby murmurs, is where he would have wanted to be, beside his loved ones, as the remains of other family members are interred here. And he is close to home. For the hero of the nation was first and foremost a son of Maitland.

That Les Darcy remains a favourite son of Maitland and is still remembered and honoured a century on brings a smile to Yanwyn Kirby’s face, as he ponders what his relative might have thought.

“He was a very shy person,” Kirby replies.

“He’d probably be a bit embarrassed but also glowing with a sense of pride and gratitude towards those who have been kind to him, and to his memory.”