What they do to steel at the hot strip mill just doesn’t seem possible.

Having seen and touched those long thick steel slabs it’s really hard to imagine them being stretched into something almost paper thin.

And yet, that’s the sort of magic they do at the hot strip mill.

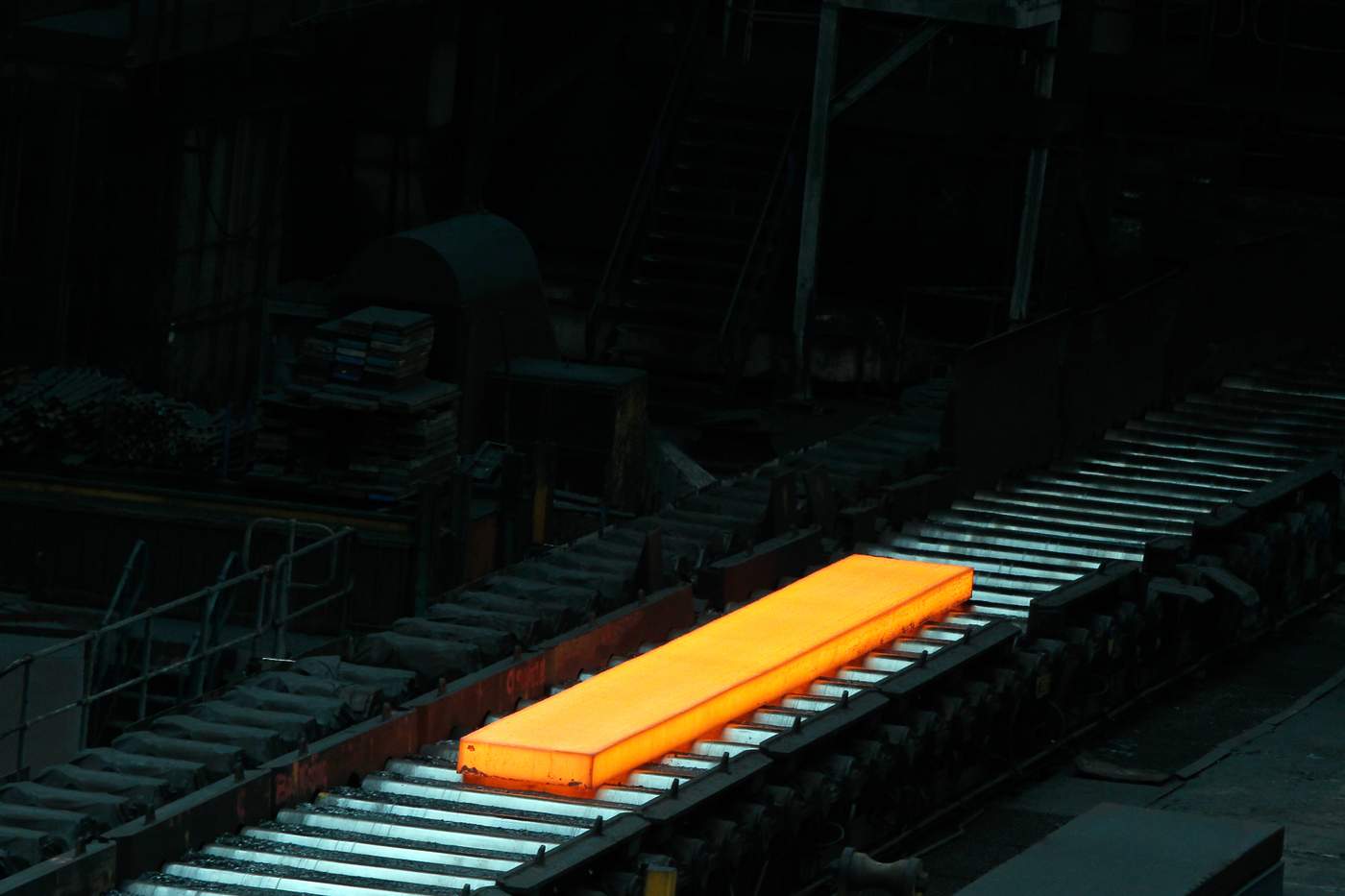

The mill takes a slab of steel of around 12 metres long and roughly 25 centimetres thick and turn it into something that could be almost a kilometre long and as slim as 1.5 millimetres.

Sure, there’s science - and brute force of machines behind it - but watching that slab get stretched out is a sight to behold.

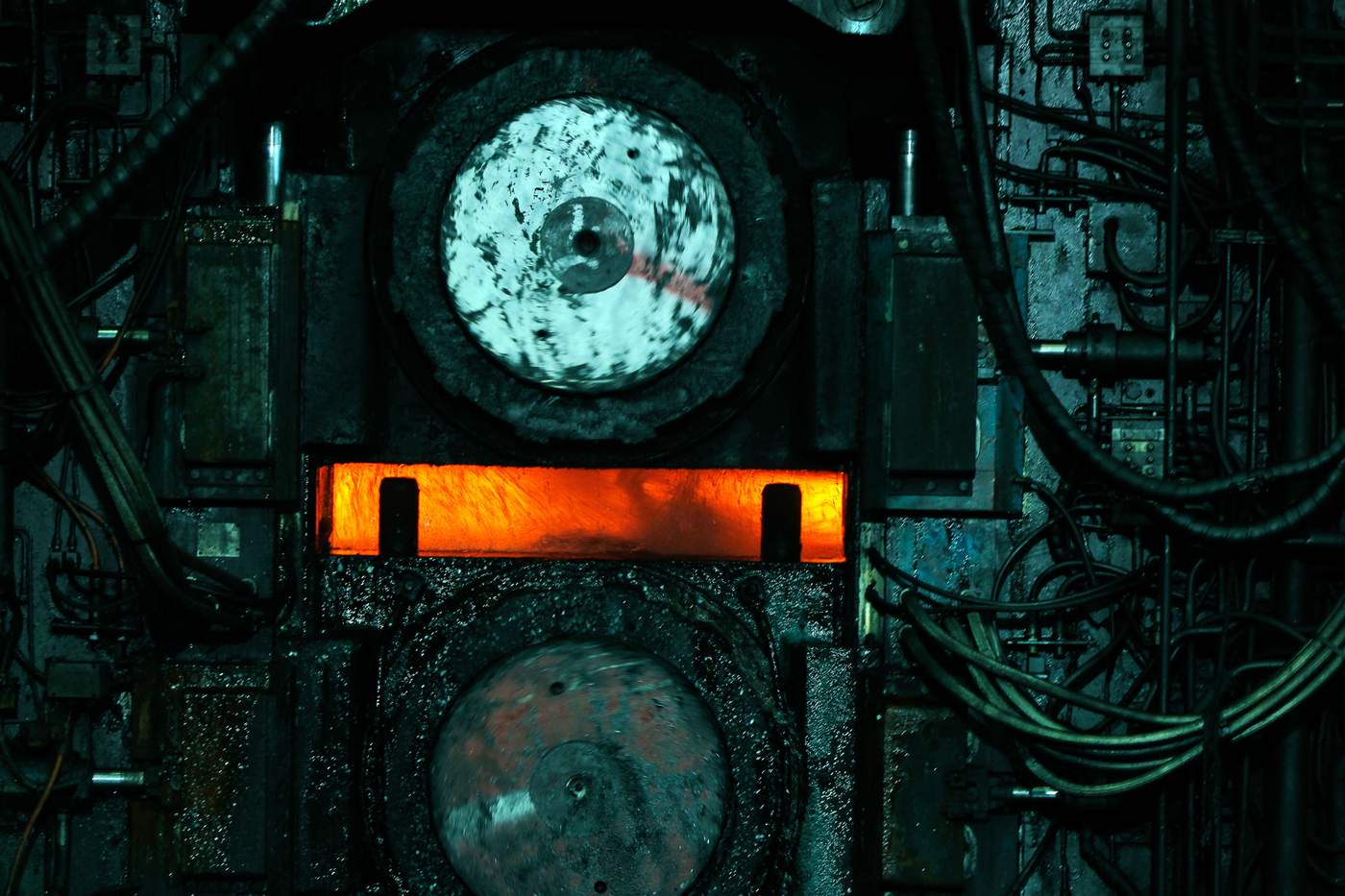

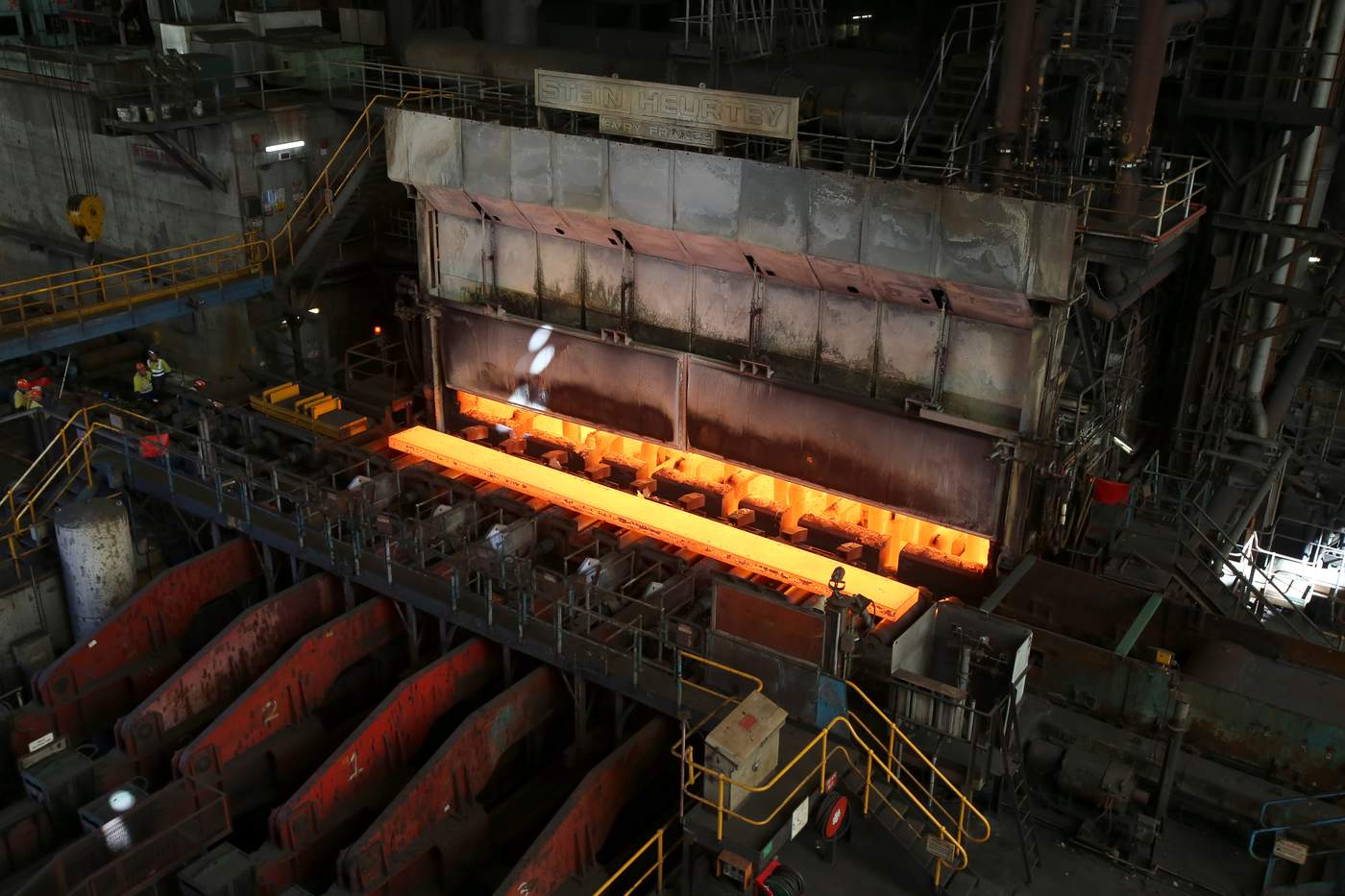

The process starts at the far end of the 800-odd metre-long hot strip mill, where slabs arrive from the slab yard and are loaded one at a time in the furnace.

Depending on what the end requirements are, the slabs will be heated (by the use of gas from the coke ovens) to between 1150 and 1250 degrees Celsius.

Once inside they slowly move through the furnace until they come out the other side three hours later. And they’re very, very hot.

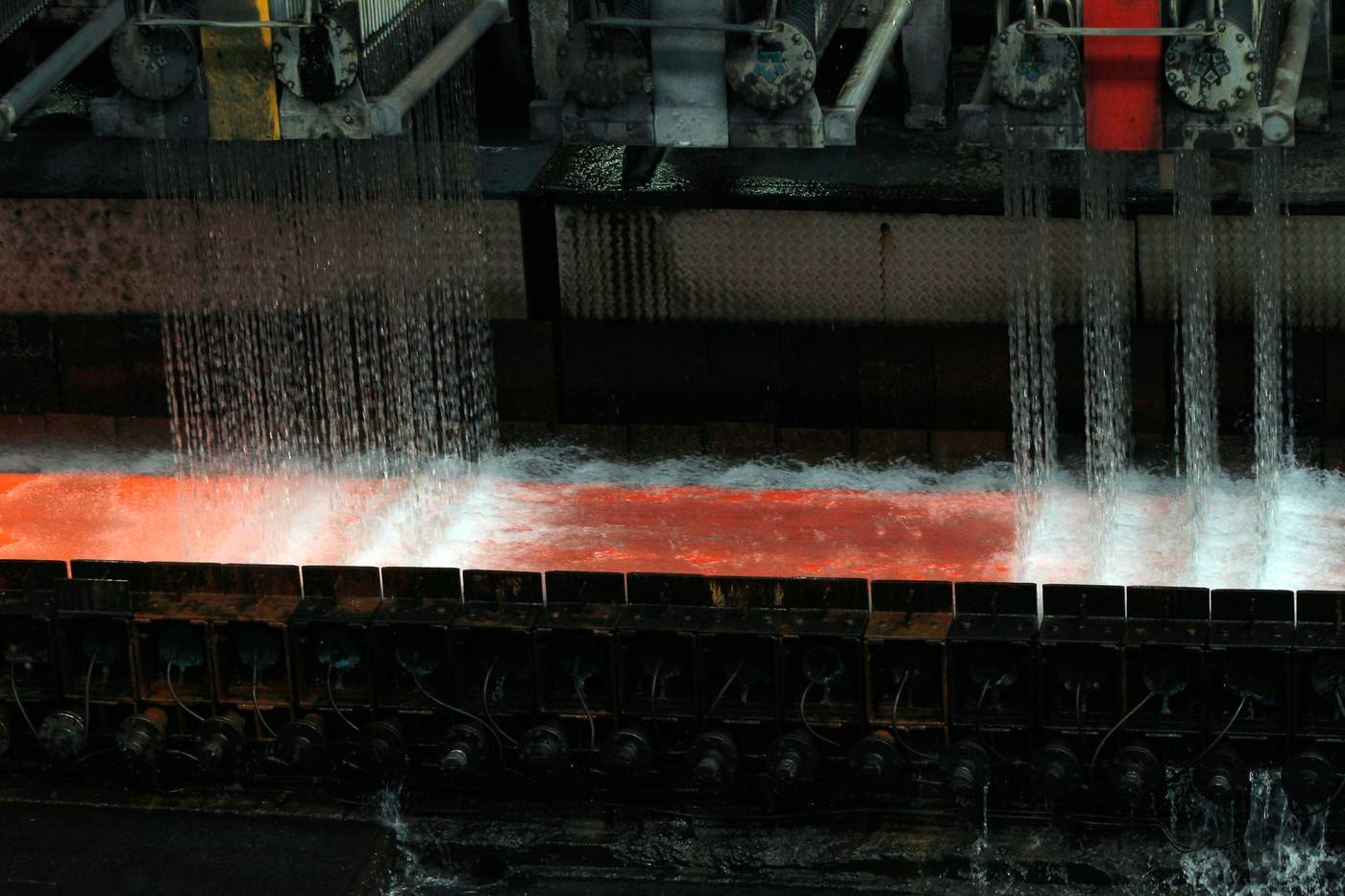

Once out of the furnace the slab is hit with a spray of water to remove the scale (a protective coating that naturally forms on the slab) before being sent down a long conveyor belt stretching several hundred metres to the roughing mill.