The steel story: the coke ovens

Journalist Glen Humphries and photographer Sylvia Liber pull back the steel curtain and take you deep inside BlueScope's Port Kembla steelworks.

04 April 2016

The cokemaking plant at BlueScope is home to a widely-held misconception about the steelworks.

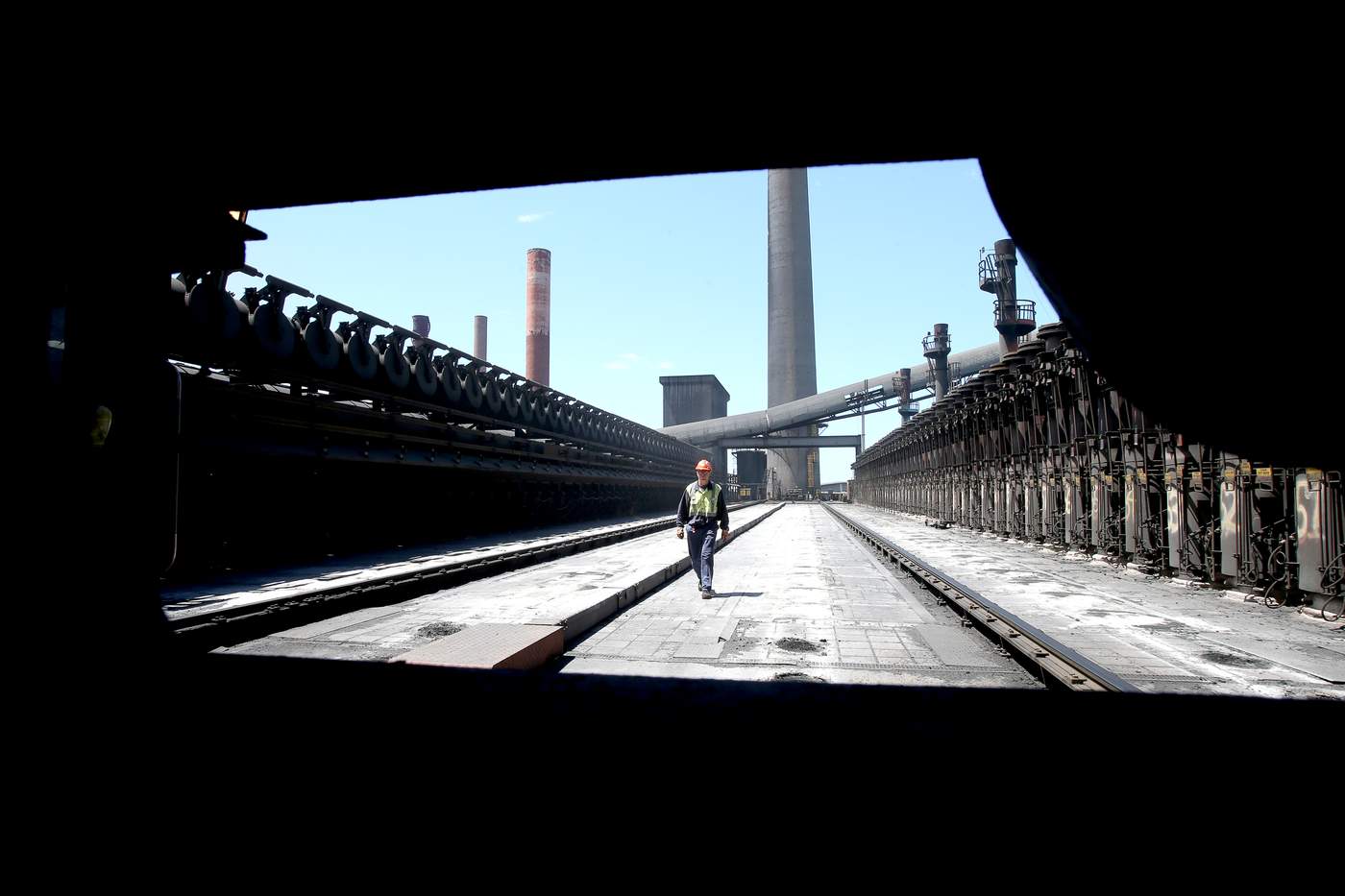

The plant, which sits at the rear of the steelworks along Flinders Street, includes a tall stack that regularly puffs out white plumes - which many people take for pollution.

But it’s actually steam, caused by thousands of litres of water poured on red-hot coke to cool it.

And it needs to be cooled – the coke comes out of the ovens at a scorching 1180 degrees and the quenching process brings it down to 80 degrees.

It’s then left in a pile to cool further before being placed on a conveyor and taken to the blast furnace.

Coke is one of the key ingredients in making iron, which is then used to create steel.

The coke starts out life as coal, most of which is sourced within the Illawarra.

Once it arrives at BlueScope the coal is blended together over seven days into a pile that weighs about 50,000 tonnes.

It’s then ground into small pieces and travels via conveyors to the top of the coke ovens.

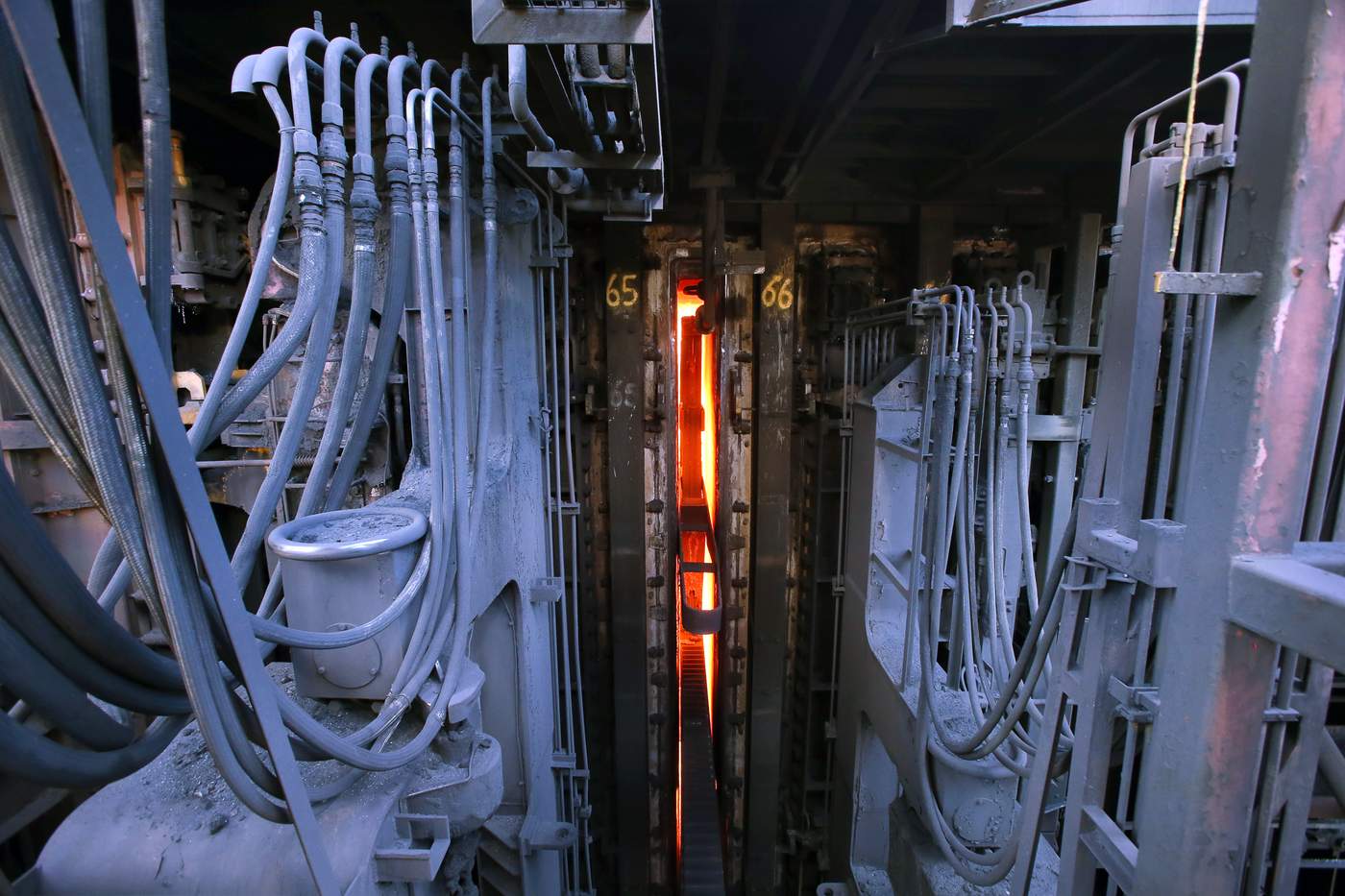

A coke oven doesn’t resembles the oven in your house. Rather, it’s a long thin slot like that in a toaster where you put your bread.

A group of ovens is called a battery (BlueScope has three of them), which resembles a long toaster pushed onto its side and with a whole lot of slots for bread.

Oh yeah, and the “bread” goes in one side but comes out the other side as “toast”.

But replace “bread” with “coal” and “toast” with “coke”.

The coal is sent to the top of a battery 40,000 tonnes at a time, where it sits in a charging car.

The charging car is a large beast that runs up and down the oven roof on rails.

Once it’s moving you have to stand in a marked walkway less than a metre wide so it can pass over you - which is a little unnerving.

The car dumps the coal into an oven and closes the top.

Then gas is pumped into the walls either side of oven – direct flame never touches the coal – and melt the coal, which reforms into coke.

After 18 hours, the cooking is done and a ‘‘ram car’’ moves into place on one side of the oven, while a ‘‘hot car’’ sits on the other side.

The ram car opens the oven door and a giant ram (see why they call it a ram car?) pushes the coke out the other side into the hot car.

When it tumbles into the car 40 tonnes of coal has become 30 tonnes of coke - and then it’s off to have cooling water poured on it.

Two-thirds of the 1.8 million tonnes is used internally by BlueScope with the excess one-third - the equivalent of 16 boatloads - heading to steel mills overseas.

The excess is unavoidable as the coke ovens need to be running constantly - to turn them off would cause damage.